A forgotten vision for Middle East peace

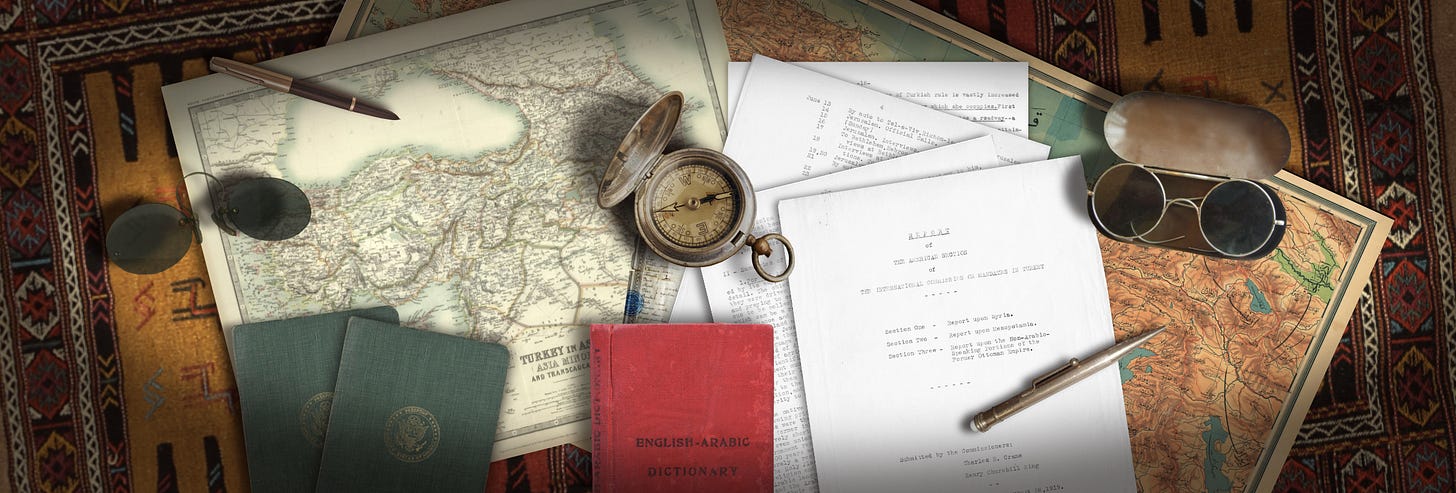

In 1919, the King-Crane Commission on the defunct Ottoman Empire issued a report one historian called ‘one of the great suppressed documents of the peacemaking era.’

Turmoil, conflict and stagnation have characterized the Middle East and northern Africa for the last 100 years. Even now, the Palestinians have no recognized state or autonomous homeland. Israel, engaged in the horrific Gaza War, is locked into tense and sometimes hostile relations with many of its neighbors, most recently its exchange of attacks with Iran. Syria, struggling to emerge from decades of authoritarian rule after dictator Bashar al-Assad was deposed in 2024, has no stable government. Lebanon remains in the grip of economic collapse and ethnic strife, while Libya boasts two rival governments.

The picture is a far cry from the hopes some held in the aftermath of World War I, when the Ottoman Empire collapsed and US President Woodrow Wilson was advocating self-determination and the establishment of a just, lasting peace. In 1919, he established a group of notables called the King-Crane Commission under the auspices of the Versailles peace process and charged it with making proposals for the disposition of formerly Ottoman-held territories.

One of the commission’s leaders was the longtime Wilson adviser Charles R. Crane, a diplomat and philanthropist who was a co-founder of the Institute of Current World Affairs in 1925. The other was Henry Churchill King, a theologian who was president of Oberlin College.

The commission’s report, kept under wraps until 1922, is largely forgotten today. But it’s intriguing to ponder what might have been if Wilson hadn’t fallen ill in 1919—incapacitating him to the end of his presidency in 1921—and the document had served as a basis for resolving the vexing issues in the region. Could things have been different, better?

After the war, the remaining colonial powers of the time—Britain, France and Italy—each had its own vision of how the geopolitical map should be drawn. Wilson’s idealism envisioned something different. He was against a mere reallocation of the region by external powers, as southeastern Europe had been reorganized under the Treaty of Berlin in 1878 and Africa divided at the Congress of Berlin (1884). Britain and France—with the blessing of Russia and Italy—had already settled on a similar fate for the Ottoman territories under the secret 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement.

By contrast, Wilson sought to develop mechanisms of self-determination, a very radical idea at that time that challenged the ascendance of the old empires. In his landmark Fourteen Points speech in January 1918, he had called for “an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development” for peoples previously under Turkish rule, adding they should be “assured an undoubted security of life.”

The key was the process: Rather than European colonial powers bargaining and swapping territories around a table in Paris, Wilson wanted to understand how the people of the region saw their own future. He ordered the commission’s members to travel and “acquaint yourselves…with the state of opinion there with regard to these matters, with the social, racial and economic conditions, a knowledge of which might serve to guide the judgment of the [Paris] conference.” Their perspectives would inform a rational division of the territories in question and “put the development of their people under the guidance of governments which are to act as mandatories of the League of Nations.” The commission’s work, Wilson added, must be accomplished “to promote the order, peace and development of those peoples and countries.”

And travel it did. Over 42 days, the commission—officially called the 1919 Inter-Allied Commission on Mandates in Turkey—visited 36 cities and towns, read numerous petitions and interviewed 1,800 people. The Middle East specialist James Zogby, co-founder of the Arab American Institute, said the King-Crane Commission essentially carried out “the first survey of Arab public opinion.”

The final 40,000-word King-Crane Commission report was submitted in August 1919. By then, however, an ailing Wilson—who suffered a debilitating stroke in October 1919 that was kept hidden from the public—was already playing an increasingly marginal role in the Paris talks, while the US Senate was balking at ratifying the Treaty of Versailles and US membership in the League of Nations. Most historians believe Wilson never actually read the report, and without his endorsement, it was relegated to the State Department’s archives, where it was discovered by the journalist Ray Stannard Baker in 1922. In August 1922, Baker published a summary of the findings in The New York Times; Editor And Publisher magazine printed the complete report in December.

The complexity of the issues at hand and differences of opinion among commission members made it difficult for them to include a unified set of recommendations. Although it was clear the peoples across the region sought immediate independence, the commission took a measured approach.

It recommended that Greater Syria be placed under the mandate of either Britain or the United States, with a constitutional monarchy. Lebanon was to have considerable autonomy within Greater Syria and, eventually, a French mandate. The report said the United States should be given the mandate for a new International Constantinopolitan State, which would encompass most of Anatolia. Mesopotamia would be under a British mandate.

Notably, the report did not recommend a separate Jewish state because of widespread hostility to the idea throughout the region.

Although the very idea of mandates could be seen as virtually a form of colonialism, the historian Andrew Patrick, in his exhaustive monograph America’s Forgotten Middle East Initiative, argues that the report was consistent with Wilson’s principles and closer to self-determination. “A mandatory power, as was written in the commission’s final report, ‘should come in not at all as a colonizing power in the old sense of that term,’” he writes, “but as a ‘Mandatory under the League of Nations.’”

“The commissioners emphatically argued that a mandate should not be treated as a colony,” he adds. “The mandatory power’s duty was to ‘educate’ the peoples of these regions in ‘self-government’ and help them create ‘a democratic state’ that protected its minorities. The mandates would help develop an ‘intelligent’ citizenry with a ‘strong national feeling’ whose overarching goal was ‘the progress of the country.’”

While the report did not advocate complete independence for any of the countries in the region, it did envision a democratic future for them. That was almost certainly a concession to the colonial powers at Paris and recognition that any recommendation for complete independence would have been rejected out of hand.

In the end, the process was dominated by the other major powers, which had already reached their conclusions. “When it appeared that the commission was going to have little impact on decisions made in Paris,” Patrick writes, “more populist nationalism emerged. The commission had even less impact in Paris, where the report was all but ignored.”

Charles Crane explained in the 1930s that “the interests that were opposed to the report, especially the Jewish and the French, were able to persuade President Wilson that, as Americans were not going to take any future responsibility for Palestine, it was not fair that the report should be published so it was pigeonholed in the archives of the State Department.”

Some have since recognized the King-Crane Commission report’s significance. The American journalist William Ellis called it “one of the great suppressed documents of the peacemaking period.” But it remains a forgotten blueprint for a troubled region to this day. On August 5, 2025, The New York Times front-paged a story on the Sykes-Picot Agreement to illustrate how Britain and France had changed their policies toward Palestine away from colonial domination to recognizing an independent Palestinian state, but made no mention of the King-Crane Commission or its report.

Counterfactuals are illusory by nature, and it can be argued that the Wilsonian idealism at the heart of the King-Crane report could not have withstood the failure of the League of Nations, the stresses of the Great Depression and the rise of militant fascism. But the commission’s approach was ahead of its time, a noble effort to include popular sentiments in the calculus of geopolitics.

“The tragedy of the King-Crane Report lies not in the failure to implement its recommendations,” the historian Richard Drake wrote in 2014, well before the current Middle East turmoil, “but in taking no notice of the document at all.”

“It remains the best historical source available for understanding Arab concerns about the Middle East in 1919,” he added. “We live today with the consequences of having ignored the Arabs at that fateful moment.”

Daniel Warner earned his BA in philosophy and religion from Amherst College and a PhD in political science from the Graduate Institute of International Studies in Geneva, where he served as deputy to the director for many years, as well as founder and director of several programs on international organizations. His book An Ethic of Responsibility in International Relations was awarded the Marie Schappler Prize by the Société Académique de Genève.

While Crane may have done many

admirable things in his life, sympathy for Jews was not among them. Here’s a letter he wrote to FDR after Hitler’s ascension to power:

The Jews, after winning the war, galloping along at a swift pace, getting Russia, England and Palestine, being caught in the act of trying to seize Germany, too, and meeting their first real rebuff, have gone plumb crazy and are deluging the world—particularly easy America—with anti-German propaganda. I strongly advise you to resist every social invitation.