Art Deco mania spreads through Paris

The movement first swept the world a century ago.

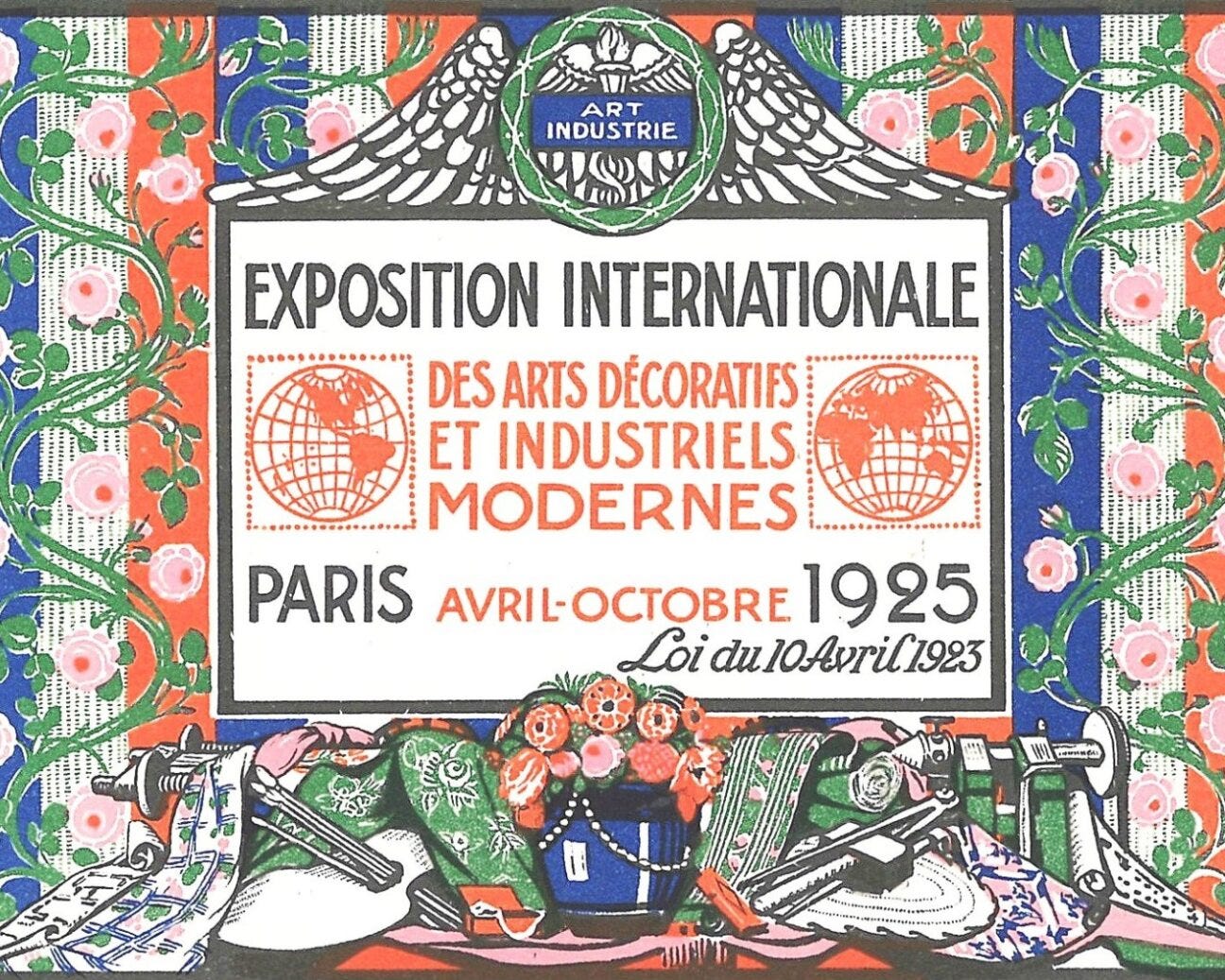

Art Deco. The words conjure images of streamlined buildings, luxurious interiors, bejeweled cigarette cases and hipless dresses. The style had been incubating in France for a decade or so when, in 1925, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts opened in Paris to show off the very latest arts, crafts and engineering. A veritable world’s fair of style, it gave us the term Art Deco.

As the Institute of Current World Affairs marks its own 100th anniversary this year, museums all over Paris are celebrating the centennial of the event that broadcast French style around the world and helped usher in the modern age. With a devastating world war behind them, the Roaring Twenties (the French call them “les années folles,” crazy years) brought a new sense of energy. Artists and artisans replaced the nature-based, intricate vegetal forms of the 1890s that had been called Art Nouveau but which now seemed out of date. The International Exhibition provided an official debut and imprimatur to a new aesthetic: streamlined shapes in architecture, bold color blocks and shapes in painting and décor, freedom of movement in fashion.

An exhibition at the Cité de l’Architecture takes visitors back to the fair, when a series of 26 pavilions on the banks of the Seine designed by some of France’s greatest living architects were outfitted by some 20,000 decorators, manufacturers, craftsmen, artists and designers. From April to November 1925, nearly 16 million visitors passed through a 57-acre architectural Disneyland stretching from Les Invalides on the Left Bank to the Grand Palais and Place de la Concorde on the Right. The Eiffel Tower (a remnant of Paris’s 1889 world’s fair) was emblazoned with the auto manufacturer Citroën’s name and logo in lights.

In this city within a city, the rules required that every object had to be “modern and original” and every structure should “respond to new architectural challenges.” The latter criterion wasn’t frivolous; it stemmed from a yearning to rebuild after the destruction of World War I. Postwar competitions for new housing led Robert Mallet-Stevens, Tony Garnier and other architects to publish plans for modern or industrial cities—housing and urban planning were top of mind. The 1925 expo was a key showcase for their ideas; their constructions at the fair enabled the public to experience model buildings.

Among the thousands of foreign visitors to the fair was MGM’s art director Cedric Gibbons. He returned to Hollywood an Art Deco evangelist. For the next decade, the studio’s movies would feature Art Deco film sets, spreading the style’s association with glamour. In 1929, Gibbons designed the movie industry’s ultimate prize: the quintessentially Deco Oscar statuette.

Sadly, none of the 1925 fairground pavilions survive, but the Cité’s exhibition has reconstructed a sense of being there with maquettes and 3-D imaging. Architectural drawings by Mallet-Stevens and Garnier along with those of Auguste Perret, Pierre Patout and Le Corbusier are joined by photographs of the installations, the crowds, even the parties. The river Seine itself became a venue a century ago when the superstar dress designer Paul Poiret transformed a floating barge into a plush haute couture showroom. It would be his swansong; he soon would be eclipsed by Coco Chanel.

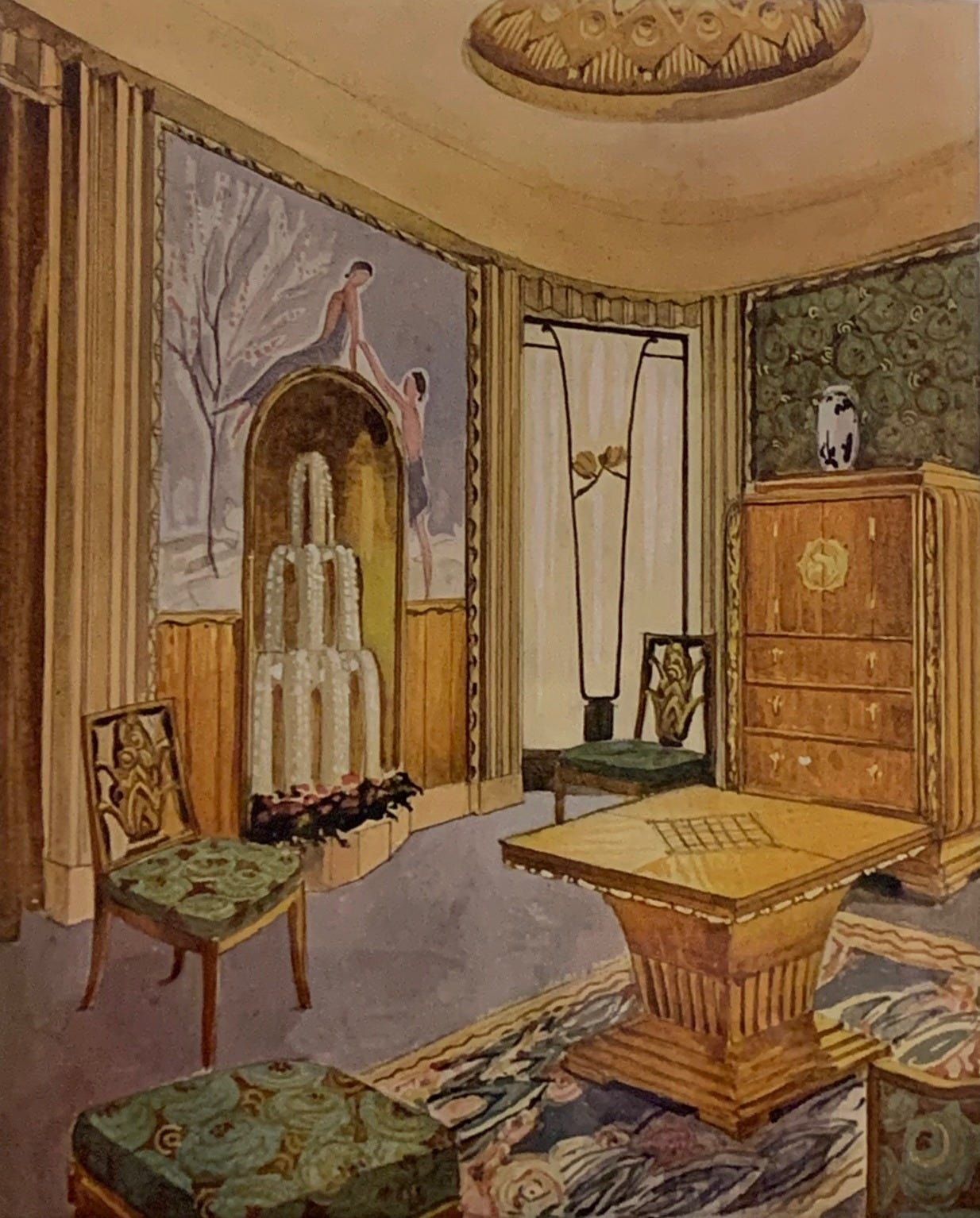

Poiret’s dresses are only one facet of craftsmanship on view at a blockbuster Art Deco centenary show at the Musée des Arts Decoratifs, (MAD to Parisians). The show is an almost overwhelming parade of objects from ceramics to wallpaper, glassware to lighting, ultra-modern furniture to the phenomenal jewelry epitomized by Cartier and Boucheron. In every category, geometric designs chase away the tendrils, vines and arabesques of the turn-of-the-century’s Art Nouveau style.

The new furniture’s spare, clean lines shouted ‘Modern!’ while elevating the most traditional crafts. Their air of simplicity belied the use of materials that were the height of sophistication—new techniques allowed for unheard-of combinations: aluminum, tropical woods, ivory, shagreen, mother of pearl, quartz—the MAD exhibition even includes a writing table sheathed in python skin. Modern to be sure, but the guiding word of the day was “decorative.”

In an age of luxury, transport was no exception. Ocean liners such as the Normandie, launched in 1932, became floating showrooms for Deco designs, from the paneled and mirrored walls of its dining rooms right down to the sugar bowls and coffee spoons on the museum’s recreated on-board table settings.

In addition to MGM’s movies, those ocean liners carrying Europeans to America would provide a vector spreading enormous influence to the United States. The resulting 1930s design style, christened “Streamline Moderne” with its long lines, curves and even nautical nods, was already called “le style paquebot” (ocean liner style) in France.

Cross-fertilization of architects and designers from Paris and New York reached far beyond their respective harbors. Philadelphia, Chicago, Cincinnati and other cities would sprout Deco buildings: train stations, movie theaters, department stores and especially skyscrapers. Perhaps the crown jewel of them all would be New York’s Chrysler Building, completed in 1930.

While the construction of those buildings relied on new technology, it also emphasized artistic detail. Take, for example, the Empire State Building with its wainscotting, terrazzo tiles, elegant light fixtures and bas-relief walls. As their French counterparts had done in Paris, American architects and artists made design nods to ancient Greece and Rome, elevating the buildings from the merely functional. From towers to toasters, the Streamline style took over industrial design in the United States.

No household item was left out: alarm clocks, radios, vacuum cleaners, automobiles. After the Wall Street crash of 1929, economic necessity led to the replacement of expensive materials with factory-made products. The Deco style gained a particularly American twist, spreading throughout the country with every one of those clocks and radios. Choosing the stylistic vocabulary of Art Deco had another important goal through the 1930s: looking forward with confidence. Art historians repeatedly refer to the style as embracing the future. Chrysler Building architect William Van Alen (who studied in Paris) is said to have declared: “No old stuff for me!”

The effects would ripple across the rest of the globe. In Japan, when Toyota put out its first production car, the AA sedan, it was a virtual copy of Chrysler’s Deco-inspired DeSoto AirFlow. Deco was already in vogue there, partly thanks to Japan’s crown prince and princess who brought it home from their long stays in Paris. Ditto India’s maharajahs, who invited French architects they had met in Paris to build their Deco palaces—cinemas, banks and even government buildings took up the style, too.

Back in the United States, Chicago hosted the World’s Fair of 1933, whose theme, “Technological Innovation,” was a direct descendant of Paris’s 1925 fair. The main exhibit, “Homes of Tomorrow,” showcased new building materials and modern household conveniences. Despite the shadow of the Great Depression, the public responded to the optimism inherent in Art Deco style, and the accessibility—both cultural and financial—of goods that didn’t feel impersonal despite being mass-produced.

This month, Art Deco is being highlighted in numerous other exhibitions around Paris, including a show at the Forney Library featuring the style’s influence as spread by Paris’s great department stores, where renowned decorators led workshops for home furnishings. Small museums devoted to single artists, such as the Musée Zadkine housing the atelier of the Franco-Russian sculptor Ossip Zadkine (1888-1967), are also fueling Paris’s renewed Art Deco mania.

Whether it’s the centenary or simply the cyclical nature of trends, Art Deco seems to be coming back. From interior decoration magazines to social media, and just this past August on Manhattan’s skyline, where the new JP Morgan Chase Tower seems to distil a reading of Deco.

MAD’s exhibit culminates in a grand finale: an entire railroad car of the Orient Express, newly refitted in almost inconceivable luxury by the contemporary architect Maxime d’Angeac. Featuring intricate craftsmanship and functionality that hew perfectly to the Roaring Twenties aesthetic, it’s a prototype for the 142-year-old line’s new trains scheduled to launch in 2027, propelling a 21st century Art Deco style into the future.

“Paris 1925, Art Déco and its architects” is at Cité de l’Architecture until March 29.

“1925-2025, a Hundred years of Art Déco” is at MAD until April 26.

“Les Ateliers d’art des grands magasins” is at Bibliotheque Forney until February 28.

“Zadkine Art Deco” is at Musée Zadkine until April 12.

Elizabeth Wise is a former correspondent for The Associated Press and The Economist Group.

Really lovely story! Thanks for this!