ICWA@100: Out of Ethiopia

Smith Hempstone takes an adventurous road trip from Addis Ababa to Nairobi in 1957.

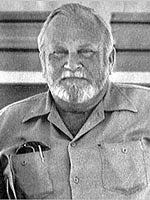

Smith Hempstone was a champion of democracy. He worked as a foreign correspondent in Africa, Latin America and Europe before becoming editor-in-chief of The Washington Times. Appointed ambassador to Kenya in 1989, Smith vocally advocated for a free vote at a time when opposition parties were banned in Kenya. His encouragement and continued push for multiparty elections earned his efforts the label “bulldozer diplomacy” in the Nairobi press. He later wrote in his Rogue Ambassador: An African Memoir (1997) about that criticism, the pushback from Daniel arap Moi’s government, and two attempts on his life. Kenya finally did host a multiparty election in 1992, shortly before the end of Smith’s tenure as ambassador.

In addition to his Nairobi memoir, Smith penned several books including Africa, Angry Young Giant, Rebels, Mercenaries and Dividends, A Tract of Time and In the Midst of Lions.

During his four-year fellowship in Africa (1956–1960), much of it in the company of his wife Kitty, Smith wrote 181 dispatches from dozens of countries. Some chronicle historic events, such as the transition to independence in Congo, Rwanda and Burundi. In others, Smith—who first went to Africa on the advice of Ernest Hemingway—introduces future leaders, such as Kenneth Kaunda, future president of Zambia. All of his essays are colorful windows into a bygone era. In this 1957 account of a rugged trip from Ethiopia to Nairobi, Kenya, he writes a highly entertaining dispatch with tantalizing mentions of an interview with Emperor Haile Selassie and Vice President Richard Nixon’s visit to Ethiopia.

NAIROBI, Kenya (April 1957) — “BORDER CLOSES MARCH 15,” read the cable, “YOU MUST REACH OYALE NOT LATER THAN MARCH l AND YOU MUST TRAVEL IN CONVOY.”

It was signed by the provincial commissioner of Kenya’s desolate Northern Frontier Province, one of the last demigods of the British Empire, ruling a kingdom larger than England, Scotland and Wales, a man from whose decisions there is no appeal except to God.

“Terrible fellow,” said Ronnie Peale, director of the British Information Service in Addis Ababa, between munches on his cold pipe. “I should get cracking toward the border immediately, if I were you.”

Out the window went plans to cover the Nixon visit, the schedule that called for us to cross the Ogaden desert to Somalia and thence down to Kenya, hopes for lengthy, high-level discussions in the Ghion bar with retired institute fellow Dave Reed, peripatetic correspondent and Boswell to Checkers’s master.

“Go by way of Neghelli,” Ronnie said as we bid him farewell. “It’s a bit rougher and longer than the direct route through Dilla, but at least you’re sure to make it that way. If the rains catch you on the Dilla road, you’ll never get through.”

We thanked him and dashed off to do our last-minute outfitting for what we knew would be a brutal trip over a road that few trucks, let alone passenger cars, will attempt. Our purchases included five-gallon jerry cans for gasoline, a shovel, a tow rope, a tire repair kit, a wash basin and canned goods.

After an 11th-hour audience with the emperor the following morning, scattering forwarding addresses around town and liberating the soap and toilet paper from our hotel room, we shoved off to the south.

The day was bright and glistening after an all-night shower, the air fresh and bracing. With firm jaws and bold hearts, we crossed the Awash and lurched through the lake country. Any connection between this area and any other lake district in the world is purely coincidental. Lakes Zwai, Langano, Hora Abyata, Shala and Awasa, aside from being unpronounceable, are inexcusable.

They sit flat and waveless, their oily surfaces merging into the soda flats, surrounded by mile after mile of baking bush and scrub thorn. They give pleasure only to the bilharzia and the crocodiles who inhabit them. But the road wasn’t bad; the weather, although getting hotter all the time, not impossible; and we passed without incident through the country of the fierce Arussi Gallas, skipped through the great cities of Shashemene and Yirgalem, and came to rest as the light was failing and the rain falling at the Sudan Interior Mission in Wondo.

The missionary, a Canadian with a Joe Palooka physique [comic strip character of a big, good-natured prizefighter]—he turned out to be a reformed hockey star—took us in, fed us and, after a hearty breakfast the next morning, accepted my baseball and mitt in return for his hospitality (I always carry them; it pays to be prepared) and pointed us in the general direction of Neghelli. There was a Norwegian mission and gas for sale there, he said. We would be there that night.

As we turned to the southeast, the road dipped lower and lower into a tropical jungle filled with screaming birds and long-haired monkeys with black bodies and white-tufted tails. The road was dirt and the surface was good. In the morning, we passed two villages. At each, I had to produce handfuls of documents before the police would move the roadblocks and let us pass. This is one of the gold-mining areas of Ethiopia. The mines are worked by prisoners, and the government does not encourage casual visitors.

We passed an Imperial Highway camp—the advance guard of the construction crews—and the road, which had been good, deteriorated immediately into a boggy trail pocked with huge holes filled with water. Each mile we went on, the road narrowed, the jungle closing in, compressing it between huge green hands. As the road got narrower, the holes got wider and deeper. At some, we cut branches and filled with stones and dirt; at others, we put the car in second and blasted on through.

At noon, I blasted when I should have shoveled. We were hopelessly mired in a three-foot bog, the water lapping in over the running board. Always a gentleman, I put all the blame on Kitty, thoughtfully showed her how to put stones under the wheels without getting wet above the knees and, squaring my shoulders, walked back down the road for help.

After a quarter of a mile, I met a citizen clothed in a loincloth, with filed teeth and a spear. I explained our difficulty. He smiled and shook his spear. I smiled and patted the revolver in my belt. We were soulmates. We walked back to the car together.

On the way we were joined by a scabby gentleman in a ripe goatskin who had no teeth at all and carried only a stick, no spear. Soulmate explained the situation to him, and he clucked understandingly.

Soulmate whistled softly when he saw the car sunk in above its hubcaps. He said something to the Ripe Goatskin, and the old man slipped off into the jungle. Soulmate sat down. I sat down. Kitty, who was beginning to look as if she wished she had married anybody but me, leaned against the car.

Goatskin reappeared with a baker’s dozen of his fellow lodge members. There was a decent amount of soft whistling at the height of the water and a certain amount of spear shaking. Then we began to push. Nothing happened.

We filled with dirt and rocks and pushed. Nothing happened.

A genius in the crowd cut a channel from the bog off into the jungle, and the water started to pour out.

After unloading the car in the rain, draining the bog, filling it with stones and dry dirt, cutting down the edge of the incline, putting steel mats under the wheels and pushing and prying, the car came free.

We reloaded, passed out some coins with bonuses for Soulmate and the Ripe Goatskin, shook hands all around and expressed the hope that we might see them all someday in Washington. And off we went.

We began to hit more streams. Everybody else builds bridges by putting two supports across the stream and covering them with logs laid parallel to the streambed. Ethiopians simply fell a number of logs across the stream and push them together. We negotiated five or six of these bridges.

The seventh was a murderous-looking thing bridging one arm of a swamp that crawled through a patch of jungle choking the gorge between two abrupt hills. Halfway across, one of the logs gave way. We came down on the gearbox with a resounding smash, the right rear wheel suspended and spinning slowly over the swamp. We jacked, filled and inflated the tires to the bursting point to try to raise the car off the gearbox. It was dark, it was raining and we could hear a leopard coughing down at the bottom of the lugger.

We got back in the car and broke out our last bottle of scotch. While the mud with which we were caked from head to foot dried a bit, we had a drink to Ronnie Peale. Then we had one to the Imperial Highway Department. Then we had one to their Imperial Majesties and to the leopard in the lugger. By mutual consent, we skipped dinner, crawled onto the soaking mattress in the back of the car and went to sleep.