ICWA@100: The Communists lay siege to Beijing

Doak Barnett reports from inside the city in 1949 on its fall to the People's Liberation Army.

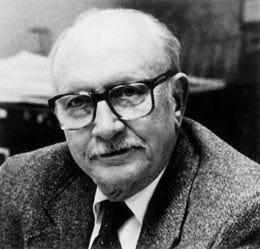

Doak Barnett, one of America’s leading and most prolific China experts, was a devoted teacher and firm believer in the importance of productive Sino-American relations. Following his fellowship in China from 1947 to 1952, he served as a public affairs officer at the American Consulate in Hong Kong and then as an associate for the American Universities Field Staff, ICWA’s sister organization, until 1955. He went on to become a professor of political science at Columbia University in 1961. In 1966, he was the principal witness in a Senate Foreign Relations Committee review of China policy, credited with influencing Presidents Nixon and Johnson to work toward opening relations with China. Doak then spent 13 years as a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute, after which he became professor of Chinese Studies at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies. He is the author or editor of more than 20 books, including China’s Far West: Four Decades of Change (1994).

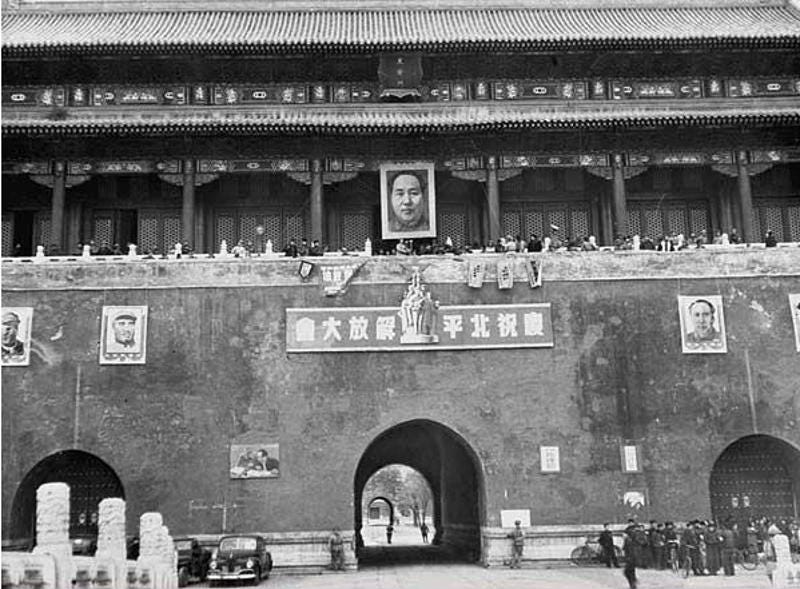

Following World War II, civil war erupted in China between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT). Mao Zedong, leader of the CCP, declared the foundation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In that year, Doak reported on the party’s seige of Beijing from within the city. Beijing’s fall to communism led the United States to suspend diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China until the 1970s. Today, the CCP is China’s sole-ruling party with over 90 million members.

PEIPING, China (February 1949) — On the morning of December 17, I left Nanking aboard a C-47 bound for Peiping. None of the 13 persons aboard the plane knew whether or not we would be able to land at our destination. Four days previously, the Communist Army had opened an attack on Peiping. The city’s west airfield was known to be out of commission. The south field was reported to be under fire from Communist artillery, and Red troops were said to be closing in everywhere around the city. We crossed our fingers and hoped it would be possible to land, and fortunately it was.

We landed on a deserted concrete strip of no-man’s-land. The Nationalists had already evacuated South Field, leaving it littered with old equipment, abandoned personal possessions and relics of the Chinese air force, but the Communists had not yet moved in to take over the shambles. The soft thud of exploding mortar shells sounded nearby as we stepped out of the plane, so we hastily climbed into the vehicles sent out from the city to meet us and wound our way through retreating troops and defense barricades into the surrounded city of Peiping.

In the month and a half since I landed on South Field, many changes have taken place in Peiping. Yesterday the first troops of the Chinese Red Army marched into the city, and Peiping changed from Nationalist to Communist hands. This letter is a report of some of the things that have happened to Peiping and its population during this eventful period. It is a report of a siege, a surrender and a political turnover as they have affected one of China’s most important cities during a critical period in the Chinese Civil War.

The siege of Peiping began on December 13 and lasted 40 days. In an age when military technology is characterized by rockets and atom bombs, it may be difficult to realize the defense value of a mud and brick city wall even when, like the Peiping wall, it is 40 feet high and broader than Fifth Avenue. In China, however, a city wall is still a formidable defense against infantry attack, and retiring behind the Peiping wall gave [Nationalist commander General] Fu [Tso-yi] and his troops temporary sanctuary.

In adopting snail tactics, moreover, General Fu had more than a mere wall protecting him. He made the whole city of Peiping his hostage. As one Chinese observer expressed it, “General Fu Tso-yi holds a beautifully delicate and priceless vase in his fingers. If anyone tries to take it, it will be destroyed.” It was generally believed that the Communists not only respected the popular sentiment attached to Peiping but had an even more practical reason for wanting to capture the city intact. Political observers predicted that the Communists would establish their national capital in Peiping.

With a knowledge of these facts and a confidence that no one would dare desecrate their city, the people in Peiping settled down for a long siege after the first noises of battle had died away. They shrugged their shoulders and went back to the normal business of buying, selling, eating, procreating and dying. “Peiping has seen many conquerors over the centuries and doesn’t pay a great deal of attention to most of them,” one philosophical citizen said to me. “People try to carry on as usual.”

During the siege, people in Peiping did carry on as usual to the best of their ability. At times they showed emotions of nervousness (No one has ever shelled Peiping before!), annoyance (We can’t even buy pork for New Year’s!) or disgust (Why tear down the archway of Eternal Peace Avenue? They’ll never finish building the airfield there anyway!), but there was never any mass fear or hysteria even during the most tense moments. The prevailing attitude was resignation, even though conditions of siege and martial law temporarily destroyed much of the city’s usual charming placidity and saddled ordinary people with a heavy economic burden.

The net effect of all that happened in Peiping during the siege was slow but definite social disintegration. No effort was made by the authorities to explain to either soldiers or civilians what was being done and why. On top of all the past accumulated dissatisfaction with the ineffective Nationalist regime, the deterioration caused by the siege resulted in the complete undermining of whatever popular support the Nationalist regime had previously enjoyed. A will to resist did not exist among the rank and file of either soldiers or civilians. With few exceptions people wanted one thing: peace at any price. They hoped that the Communists would take the city soon and finish the siege. Only a small minority looked forward to Communist rule with enthusiasm, but the majority, although skeptical of what Communist rule might mean, no longer had any reservations about accepting Communist rule as an alternative superior to existing conditions.

The lack of any sort of excitement when the first troops marched in was striking. “The Communists have arrived,” one man said. “And prices have gone up,” said his companion. The word was passed around that a big parade would be held soon. A pedicab driver was unimpressed. “Anyone can put on a parade,” he remarked. “Even the Japanese did.” A philosophical cook observed that “the Chinese people are like blades of grass. They lean the way the wind is blowing.” The people of Peiping leaned toward the Communists, but the first reception given to the entering troops indicated that the Communists would be working in an environment characterized by skeptical pragmatism. People would wait and see what happened before they got emotional—if, indeed, they ever did.