ICWA@100: Visiting Mahatma Gandhi in colonial India

Phillips Talbot spends time with the visionary leader and his community of disciples in 1941.

Phillips Talbot’s India fellowship coincided with the country’s independence movement. He witnessed the partition of India and Pakistan and got to know the leaders of both new countries, including Mahatma Gandhi. His fellowship began in 1938 and ended in 1950, interrupted by World War II, during which he served in naval intelligence. Previously a reporter for the Chicago Daily News, after his fellowship he went on to help found and run the institute’s sister program, the American Universities Field Staff, continuing to write extensively about his region.

President John F. Kennedy appointed Phil assistant secretary of state for Near Eastern and South Asian affairs from 1961 to 1965, and he served as ambassador to Greece from 1965 to 1969, during a successful military coup. He was president of the Asia Society from 1971 to 1980 after helping John D. Rockefeller III found the organization in 1956. While serving in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, Phil worked to resolve conflicts between India and Pakistan before their 1965 war over Kashmir, Pakistan’s closing of its border with Afghanistan, between Greece and Turkey over violence on Cyprus and in Arab refugee negotiations with Israel.

Phil received a doctorate in international relations from the University of Chicago in 1954 and a bachelor’s from the University of Illinois in 1936. He is the author of multiple books, including a compilation of his ICWA reports, An American Witness to India’s Partition.

Six years before Indian independence and shortly before his deployment in World War II, Phil visited Mahatma Gandhi’s farm in the central village of Sevagram, where Gandhi was surrounded by a community of disciples. Among the other visitors were “frequently leaders of the national movement who seek guidance, inspiration, or convalescence.” From his outpost, Gandhi continued to exercise enormous influence. “Plenty of people say that they would like other leadership,” Phil wrote, “but there is no individual who can command the loyalty and following of so many of the 400 million people of India as Gandhi, and everyone recognizes that fact.”

SEVAGRAM, India (August 1941) — When I arrived yesterday morning at Mahatma Gandhi’s ashram at Sevagram, near Wardha, 36 hours’ journey north of Bangalore, the little man was about to go to lunch. Wearing a shawl over his shoulders as well as his usual dhoti, he stood on his cottage steps, leaning on his staff, watching my approach. “Mr. Talbot?” he queried. “Ah, you have come.” That is, it turned out, his favorite form of greeting. During these two days, his first words whenever I entered his room have been “Ah, you have come.” The other habitual expression that has been loosed several times comes in explanations, which he prefaces with the phrase “for the simple reason that…” It intrigued me to hear that goat’s milk is good, or the British should leave India, or the world will yet fall back on nonviolence, all for some “simple reason.”

But in the first meeting Gandhi wasted no time leading me to a verandah where 15 or 20 men and women, already seated on the floor, were being served. With a robustness of spirit that has surprised me several times, he pointed to an empty place and laughingly said, “You sit down there and you two get friendly with each other.” To my astonishment the person he indicated was an American girl whom I had met a year ago at Ravindranath Tagore’s university, Santiniketan. She was now wearing an Indian sari, and had stayed nearly a month with Gandhi. The food we were served—well-cooked fresh vegetables, bread and butter, hot milk, and golden dextrose—was of a much higher standard than some I have eaten elsewhere in my wanderings, and I commented on the fact.

Gandhi, who was dealing out special potions for his current crop of patients, agreed that he had formerly lived on about $2 worth of food a month but had now increased the amount and quality to $5 worth. That is more than twice as much as Bishop Packenham Walsh spends. Many of the vegetables at the Gandhi ashram are grown on the 200 acres of land that the Mahatma was given by a coworker. Besides the crops, the ashram keeps a number of cattle and goats (Gandhi still drinks goats’ milk, of course). That is why good food can be obtained for the money spent. It is prepared by some of the 40 or 50 ashramites, all of whom serve in rotation in various housekeeping jobs.

These inmates of the ashram are an interesting assortment. Their boss may laughingly call them “my lunatic asylum,” adding that “I’m the biggest nut of all.” They are divided into two classes, the permanents and those who come for a few days or weeks or months. The latter are frequently leaders of the national movement who seek guidance, inspiration, or convalescence. Gandhi considers himself a good hand at doctoring, which is one of his favorite occupations. Whenever a lender gets sick, the Old Man of Sevagram has him come to the ashram for rest and a special diet. Like any other doctor, Gandhi makes morning and evening rounds of the various ashram buildings to see his current patients. For those who come to meals, he deals out special quantities of particular foods placed around him in an array of pots and pans.

The permanents are frequently people who have surrendered abjectly to the force of Gandhi’s personality. They mimic him to the extent of their capacity and let their devotion so sway them that, as one woman nationalist is quoted as rudely having said, some wouldn’t go to the latrine without “Bapu’s” permission. From the queerest specimens that have camped from time to time in the Gandhi ashram, certain American women cannot be excluded, however. The Mahatma seems to have a fatal attraction for some, about whom, I gather, stories go on forever.

The herd instincts of the ashram are illustrated morning and evening when Gandhi walks several furlongs up the road and back. While he walks blindly with his arms about the shoulders of two friends, his head down and his eyes closed, answering questions from all sides, an entourage tramps after him, matching his speed, his slowness and his turns step by step.

He does not miss a moment to fit in an interview. At lunch today we got off on some topic, and then as we walked back to his cottage he asked me about the institute. As we stood on his verandah talking, he took out his upper and lower sets of teeth, washed them carefully, gargled and made himself ready for the afternoon’s work without missing a word I said.

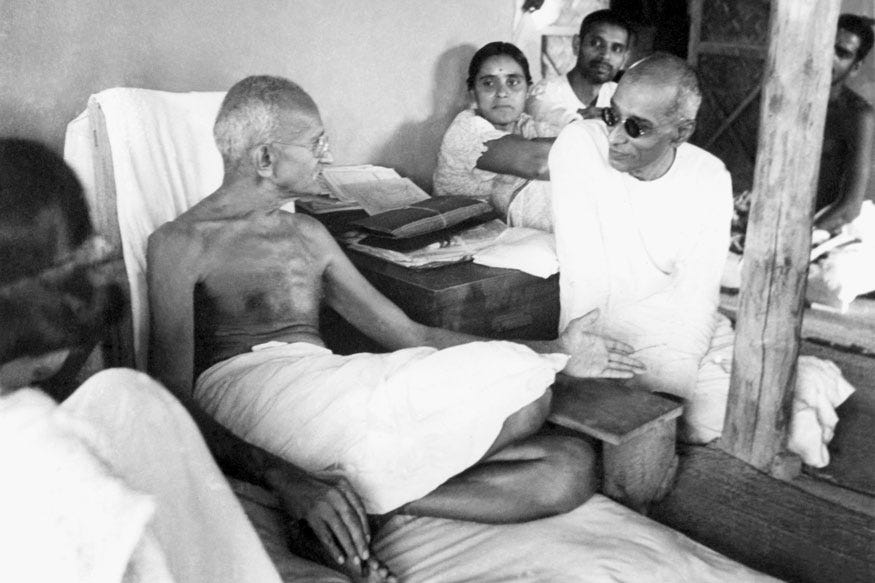

Gandhi has been called the most efficient worker in India. He has the knack of resting his body completely while his mind carries on. After lunch, for example, as he reads through his heavy correspondence, he lies almost at full length on a pad on the floor, with only a wooden support raising his head and shoulders. His wife sits at his feet, massaging his legs, while he dictates answers to his secretary or straightens up to write a note himself. He uses many postcards, and to friends signs himself “Bapu,” father. Besides the male secretary and his aging wife, two or three women members of the ashram squat around him. One may be fanning him while the others read silently.

All this is in a room ordinarily used as a hospital, since his own cottage has not yet been repaired after heavy rains. The room contains no chairs and no tables higher than six or eight inches. The only picture in the whole room is a likeness of Jesus as a youth. When I referred to it, he replied with a warm appreciation of Jesus’s religion. “But I do not mix up Christianity with many missionaries I have known,” he added, amplifying his comment with an uncompromising disparagement of the mission system. The book he has published this last year on Christian missions develops his argument more completely than he did in conversation, and I did not press him since my greater interest was in the comprehensive economic program that his associates are now putting on a national basis.

On many sides in India today one hears that Gandhi is through, finished. That his era is past, the world has gone beyond him, his old magic won’t work anymore, the hour of the youth is at hand. This old cry was sounded after the civil disobedience movement, again when he resigned from the Congress in 1934, again when the Congress working committee temporarily divided from him (soon to scurry back rapidly under his leadership) after this war broke out, and again and again and again.

True it is that in many ways he seems old-fashioned. A surprising number of his ideas, such as the conviction that Paul was the first saboteur of the religion of Jesus, can be traced to reading he did in his early youth. His judgments of people and institutions are still highly colored in his prewar experiences in South Africa. It is also true that he seemed to bungle at times and has changed his ground so that even Jawaharlal Nehru was hard-pressed to keep in line. And certainly many youthful nationalists have gnashed their teeth at the moderation he has forced upon them in this crisis, which seems to them the golden opportunity to seize the power and hold it.

Plenty of people say that they would like other leadership, but there is no individual who can command the loyalty and following of so many of the 400 million people of India as Gandhi, and everyone recognizes that fact. Perhaps after Gandhi dies someone else like Jawaharlal Nehru, if in the meantime Nehru can resolve the doubts and cross-currents of Gandhiism and socialism that have been pulling at the moorings of his philosophy for the last two or three years, can take over a similar position of leadership. Perhaps the present conservative leadership of the Congress, men like C. Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, can take over. It is also possible that the much more radical younger group can gain control of the national movement. But that is all for the future. Gandhi, who still holds the masses in his hand, is not dead, and his robust spirit and frail body that has shown such capacity for punishment may well continue to serve him for some years to come.