Kafka’s The Trial: 1925 – 2025

A century after the novel’s publication, its portrait of arbitrary justice is increasingly relevant.

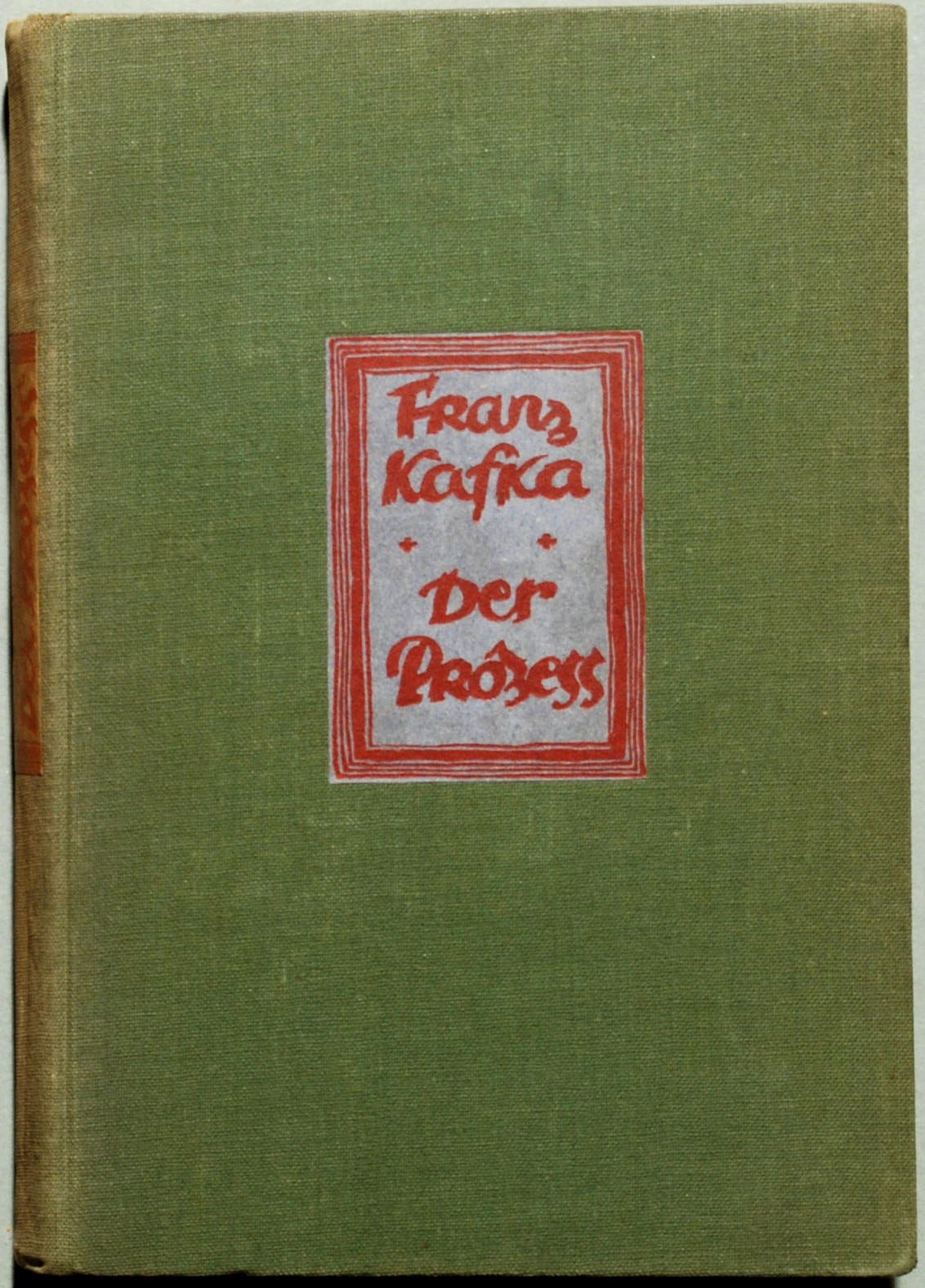

Franz Kafka’s The Trial, edited with good intentions but questionable competence by his friend and executor Max Brod, was posthumously released by a small publishing house, Die Schmiede, in 1925. It is the story of a man, Josef K., who is arrested on unexplained grounds by an unnamed authority, and, a year later, brutally killed by its agents. K. initially reassures himself that he lives in a Rechtsstaat (a state governed by the rule of law), but that reflection soon becomes irrelevant. Today, when legal guarantees are increasingly ignored not only by authoritarian states but even some countries that take pride in their constitutions, Kafka’s novel speaks with ever-increasing urgency.

The occasion for writing The Trial was the enforced end of Kafka’s engagement to Felice Bauer. Since their first meeting in August 1912, their relationship had largely been carried out in correspondence since he lived in Prague and she in Berlin, and Kafka objected to using the telephone for personal conversations. Frictions between them came to a head in the summer of 1914.

Their engagement was dissolved in July 1914, when he met Felice, her sister Erna and friend Grete Bloch in a Berlin hotel room where they accused him of treating Felice selfishly and disloyally. He described the meeting in his diary as the “tribunal in the hotel.” In the novel Kafka began writing immediately afterward, Josef K. is put on trial for offences that are never specified and seem to consist in his character rather than any definable misdemeanors.

The novel began as an extended self-analysis and self-exculpation, but it soon outgrew its origins. The “tribunal” image expanded into a minutely organized court with police agents, magistrates, judges (seen only in portrait paintings), law books, savage punishments administered by a functionary called “the Thrasher,” even a prison chaplain. K. seems to be victimized by the apparatus of a police state.

Kafka was aware of contemporary abuses of justice. France’s Dreyfus affair, in which the Jewish Army Captain Alfred Dreyfus was unjustly exiled to a French penal settlement in South America, had aroused a world-wide furor. It prompted the short story “In the Penal Colony” that Kafka, breaking off work on The Trial, wrote in September 1914. The Trial seems also to reflect the case of Mendel Beilis, a Russian Jew tried in Kyiv in 1913 after two years’ detention for allegedly murdering a Gentile child. Kafka was reading Dostoevsky in 1914, including Notes from the House of the Dead, in which the Russian novelist recounts the four years he spent in a Siberian prison camp, as well as a famous letter Dostoevsky sent his brother from exile.

The lasting fascination with The Trial is due not only to its subject matter but also its inherent ambiguity. The court that first arrests Josef K. seems benign. It does not imprison K. but leaves him free to lead his ordinary life as a senior bank official, apart from summoning him to a hearing that proceeds chaotically and ends inconclusively. When K. denounces the behavior of the guards who arrest him, the court responds by having them mercilessly beaten by the Thrasher in a disused storeroom in K.’s office building. Initially obliging toward K., savage toward delinquents, the court anticipates one of the aphorisms Kafka wrote three years later: “The hunting dogs are still playing in the courtyard, but their prey will not escape them, no matter how fast it may already be racing through the woods.’”

Rather than literally, the court should perhaps be understood as a metaphysical or even religious authority. K. might be seen as an average, unthinking person torn away from his daily routine and shallow self-satisfaction by a mysterious intervention from outside. When the court apparently withdraws from his life, K. seeks help with increasing desperation. He engages a lawyer, who seems interested only in playing power games with his clients. K. visits a painter employed by the court to produce portraits of judges from whom he learns that a genuine acquittal is theoretically possible but recorded only in legends. The accused have only two options: accept an illusory acquittal followed, perhaps the same day, by re-arrest; or prolong proceedings by legal shenanigans in the hope of postponing a final verdict.

Either way, one’s case will take over one’s life. A hint dropped by K.’s lawyer suggests that the goal of the trial is to force the accused out of his inauthentic life and into self-knowledge: “[The court] wanted to eliminate the defense counsel as far as possible, everything should depend on the accused alone.”[1] But the course of events shows that K., like others, will eventually resort to any stratagem to avoid a confrontation with himself.

Kafka introduces another twist. Victims of unjust authority may find themselves colluding with their persecutors. They may even seek emotional support in what is known as Stockholm syndrome. The Trial is sometimes called a prophetic portrayal of 20th-century tyrannies. Had Kafka lived into the 1930s, he might not have been surprised by the Soviet Union’s Old Bolsheviks who, put on trial by Stalin, confessed to all manner of trumped-up charges invented by a system they helped create. K., too, acquiesces to a system that destroys him.

In the last chapter, when the court’s executioners come for him, he is already waiting, dressed in black. They march him to an abandoned quarry and lay him flat on the ground. Briefly fantasizing about resistance, he thinks: “Logic may be unshakeable, but it cannot hold out against a human being who wants to live.”[2] But it is too late. The stubborn vital core of K.’s being awakens only when the executioner’s knife is already at his throat.

K’s last words are “Like a dog!” They express the final indignity inflicted by the court. It not only hounds K. to death but deprives him of human dignity. Dogs are mentioned at two earlier points in the novel, both times as symbols of degradation.

That theme was picked up by the Nobel Prize winner J. M. Coetzee in his novel The Life and Times of Michael K. (1983), set in an imaginary future when South Africa has collapsed into civil war. Michael K. is a physically and mentally impaired man, apparently Black, who is repeatedly arrested by police and thrust into “rehabilitation camps.” As in other novels, Coetzee conveys a visceral horror of violence, made worse because Michael K. is as bewildered as the reader (or as Josef K.) by a power struggle taking place over his head. Coetzee also pleads implicitly for Michael K.’s essential human dignity, depicting the satisfaction he feels when, having escaped from confinement, he is able to work as a gardener. The novel both echoes and responds to The Trial.

In the early 1960s, a Russian version of The Trial circulated clandestinely as self-published samizdat in the Soviet Union. It was officially published in 1965 with a foreword explaining that the novel is a fantasy which, if anything, anticipates the Third Reich. Its readers thought differently. A fantasy in which the everyday world turned out to be the façade concealing an irrational and violent world, to which people could be consigned for no reason and from which they never reappear, seemed too close to Soviet reality. And since the samizdat version was anonymous, readers assumed that it was a bitter satire based on real experience, like Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.[3]

Kafka’s rehabilitation in Russia ended during the Putin regime. The 100th anniversary of his death went largely unnoticed in 2024, as did that of Lenin’s. The leading human rights organization Memorial, devoted to recording Soviet crimes, had already been banned in 2021. One of its founders, the veteran human rights activist Oleg Orlov, went on trial in February 2024 for criticizing the invasion of Ukraine and thus allegedly discrediting the army. At his first hearing, Orlov sat down and, in protest, began reading The Trial aloud.[4] He was sentenced to four years in prison.

[1] Franz Kafka, The Trial, Mike Mitchell, trans. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009, p.82.

[2] Kafka, The Trial, p.164.

[3] See Efim Etkind, “Kafka in sowjetischer Sicht,” in Claude David, ed., Franz Kafka: Themen und Probleme. Göttingen: Vandehoeck & Ruprecht, 1980, pp.229-37.

[4] Claudia Scandura, “Kafka in Russia,” Oxford German Studies, 53 (2024), pp.143-59.

Ritchie Robertson retired in 2021 as Schwarz-Taylor Professor of German at Oxford University. His books include Kafka: Judaism, Politics and Literature (1985) and Kafka: A Very Short Introduction (2004).

Brilliant