Mein Kampf 100 years on

What is its significance for the resurgent far right?

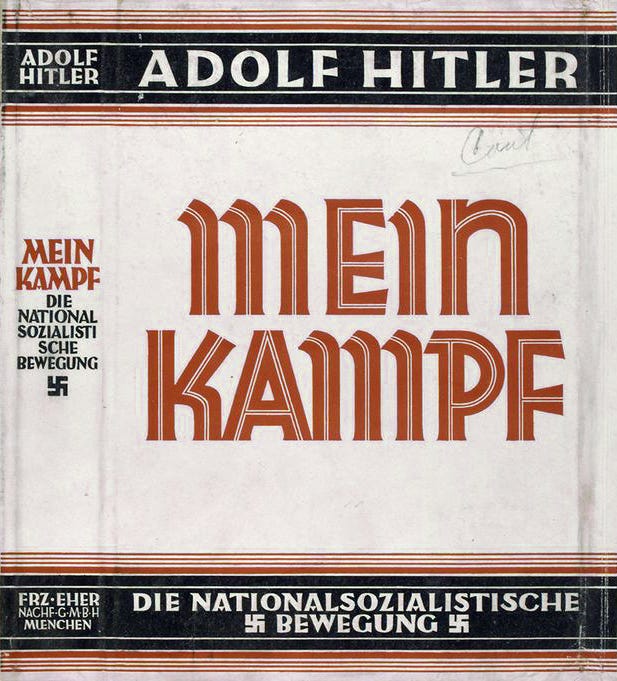

This year marks a century since the publication of the first volume of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf. It’s also a decade since the book’s German copyright expired, and with it the appearance of an important new scholarly edition. The anniversaries of both publications come at a time various forms of far-right thought, speech and action are reappearing in political culture in Germany and beyond.

It's easy to forget the political and ethical bind in which policymakers charged with policing the circulation of Hitler’s toxic text found themselves before 2015. For 70 years, standard copyright legislation had been used by the state of Bavaria—to whom ownership was entrusted by the victorious Allies in 1945—as the main tool for preventing republication. But with the expiration, a new approach was needed.

Although both general provisions of Germany’s constitution and more specific legislation regarding hate speech provided additional safeguards, it could not be ruled out that commercial publishers—possibly acting on politically nefarious or more profanely venal motives—would challenge those obstacles on allegedly educational grounds, claiming that republication was a reasonable act of public service. The increasingly compelling rhetoric of “free speech”—a favorite weapon in the arsenal of the globalized far right bent on painting democrats as the new authoritarians—and the newly disruptive factor of an inherently uncontrollable internet made reliance on traditional methods of perpetuating a ban inadequate on political, legal and practical grounds.

Opting for an essentially pragmatic, conservative strategy of embracing and domesticating what one can’t prevent, Munich’s renowned Institute of Contemporary History—which since 1949 has played a leading role researching the history of National Socialism—was entrusted with the preparation of a new annotated academic edition. A team of distinguished historians produced a heavily footnoted text that simultaneously sought to set a new standard in scholarly engagement with the book itself, offer a resource for educators to use in diverse educational settings and—by presenting the text together with relentlessly exacting commentary—to divest it of any aura it might possess for those drawn to it for the wrong reasons.

The result was a two-volume edition of nearly 2,000 pages and over 3,500 annotations that seeks both to help the well-intentioned reader understand how the text works and counter the hateful messages it contains. The introductions, footnotes and references fulfil the hybrid functions of explaining Hitler’s often obscure references to contemporary politics, connecting his rhetorical flourishes to the deeper traditions of German (and European) thought on which they drew, and underlining both the basic factual inaccuracies and ideological falsehoods integral to any reading of the text.

As a tool for teaching and research, the edition is immensely valuable. But 10 years on, can the publication be judged a success in terms of wider civic pedagogy? Is there any meaningful connection to be made between Mein Kampf, in either its original or recent iterations, and the emergence of the AfD or its European counterparts?

Ten years after Germany’s far-right party Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) seized on the European migrant crisis of 2015 to campaign on an increasingly strident nationalist platform, it’s approaching 50 percent of support in some of its regional electoral strongholds in eastern Germany. Its gains in various state elections have rendered the formation of stable, viable centrist governing coalitions at this crucial level of representation difficult and sometimes almost impossible.

In federal elections earlier this year, the AfD was compelling enough to voters to be able to compete with the old Volksparteien (“people’s parties”) of the center-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and center-left Social Democratic Party (SPD) at the national level. If the CDU currently appears more robust than the SPD—its leader Friedrich Merz is the incoming new chancellor—neither of those venerable but ossified parties appears to offer adequate answers to Germany’s economic sclerosis or its new geopolitical binds.

Unable to shed mindsets and policy prescriptions that still feel anchored in the politics of the 20th century, both have bled support to a range of challenger parties, chiefly the AfD, a real and immediate threat. It is, to say the least, ironic that in the same year the original copyright for Mein Kampf expired a decade ago, the German far right experienced the start of its most recent marked resurgence.

Like all far-right parties, the AfD channels a range of political and ideological traditions, some of which can be traced more directly to 20th-century fascism than others. On one hand, it represents the latest manifestation of a persistent potential for far-right politics that was previously most successful in the 1960s with the National Democratic Party (NPD) and found renewed expression with the Republikaner and German People's Union (DVU) parties of the 1990s.

The AfD also articulates some of the economic and social resentments engendered by the transition from the relatively stable, secure employment and social status Germans enjoyed in the industrial era (in both East and West, in different ways) to the marginality, insecurity and precarity that has been the hallmark of the post-industrial environment. The AfD channels diffuse elements of popular anti-establishment protest as well as more specifically focused hostility toward foreigners born of the migrant crisis. The latter combines the aggressive rejection of ethnic and cultural diversity with crudely reductionist, often misleading assumptions about the cost of supporting refugees and its impact on German economic wellbeing.

Cutting across all that, the AfD also contains an overtly neo-Nazi element, whose ancestors can be found in the Socialist Reich Party of the early 1950s and violent fascist undergrounds of the turn of the 20th century. That continuity is most obviously discernible in the language itself. Thuringian AfD leader Bjoern Hoecke’s references to Germany’s “thousand-year past” and “thousand-year future,” his assertions concerning the alleged genetic proclivity of Africans to reproduce at higher rates than (implicitly) white Europeans, his associated allusions to the “Great Replacement Theory” beloved of broad sections of the international far right and his slogans such as “Everything for Germany!” (Alles für Deutschland!) originally coined by the Nazi SA betray a habitual reach for a rhetorical arsenal immediately familiar to those with the literature of the 1920s.

It is in the nature of the language of the far right that many of the figures of speech it deploys—be they about “family values” or “homeland”—are shared with wider currents of conservative and reactionary thought: such is the capacious quality of language itself. But the regularity with which Hoecke reaches for terms drawn from the same lexicon as that of the AfD’s political forefathers—in his description of the AfD as a “movement” or his use of the martial metaphor of “holding out” (durchhalten)—the linguistic affinities with the pre-1945 era are impossible to explain away. The recourse to anti-Semitic terms such as “globalists” to describe the leaders of international capitalism betrays the same proclivity to explain world politics in terms of conspiracy that is familiar from Mein Kampf itself. If elements of the Thuringian AfD do not strike us as neo-Nazi, then our definitions of neo-Nazi need urgent revisiting.

The incoherence of the message, social and ideological heterogeneity and random-seeming range of articulation and expression—in street protests or manifestos, carefully choreographed media presentations—is similar to historical National Socialism too. The Nazis also drew in a wide range of socially diverse constituencies, interest groups and political commitments, ranging from marginalized rural workers to the well-heeled upper-middle class, from the ideologically literate to the socially desperate, from those hostile to change to those desperate for it.

Still, even if there are obvious affinities between the AfD and National Socialism, and we understand the AfD to be the German variant of the clear far-right threat to democracy currently blighting the Western world, the republication of Mein Kampf has no direct relevance here. The roots of the far right in Western political culture obviously go far deeper than a single scholarly publication. Indeed, they go far deeper than the original text itself.

Neil Gregor is professor of modern European history at the University of Southampton. He is the author of How to Read Hitler and, most recently, The Symphony Concert in Nazi Germany.