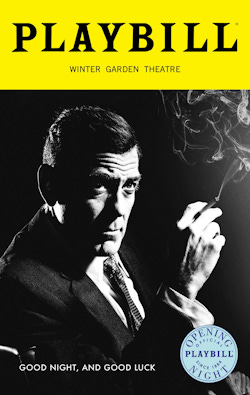

Edward R. Murrow, a journalist of a different era

Who will stand up for the truth in our time?

It was one of those modern split-screen moments: one screen bubbling with the hype and excitement of a successful Broadway play, the theater packed, the applause deafening; the other screen showing a high school classroom with a dozen honor students and a teacher gathered around a visiting journalist (that’s me) who is telling a story about the play’s main character, CBS’s incomparable Edward R. Murrow.

The link between the Broadway play and the Boston classroom was coincidental, but it revealed so much about the impact of technology on American journalism and politics, focusing on the differences between Murrow’s journalism during and after World War II and the dizzying swirl of social media, which, for many, is the journalism of today.

The teacher, a young man with a broad smile that never left his face, had read about the Broadway play, “Good Night and Good Luck,” knew about Murrow’s groundbreaking role in American journalism and introduced me with the enthusiasm reserved for a Biblical scribe. After all, I was one of the few still alive who had actually worked with Murrow.

Still, one quick glance around the classroom might have told me I’d probably selected the wrong topic for my talk; it might also have told the teacher that he’d misjudged the curiosity of his honor students. The plain fact was the young faces around us were simply blank, showing not a flicker of interest in Murrow, nor in the Broadway play that had set New York aflame with scary memories of McCarthyism, uncomfortable connections to the incumbent president (name unspoken) and whispers about a possible presidential run by the Hollywood star George Clooney, who was playing the title role on stage.

At the last moment, I could have switched subjects and, because I was in Boston, plunged into my favorite baseball prediction, shared by few others, that the Red Sox would find a way to win the American League pennant; but instead I stubbornly stuck with my topic, determined somehow to convert each student into a Murrow fan.

I opened with an obvious question: “Has anyone in this room ever heard of Edward R. Murrow?”

Not a single hand went up.

“Never even heard of him?”

No, heads slowly rolled back and forth.

I changed my approach. “Ok, when you get up in the morning, how do you know what happened during the night? Where do you turn? What do you do?”

A few faces cracked into knowing smiles. One said, “I rush to catch the bus.” Another added, “I eat a quick breakfast and run to school. I don’t want to be late.”

I realized I’d asked the wrong question. Trying again, I said, “Do you have a favorite journalist?” I looked from one student to another, hoping for a meaningful response. But again I saw nothing but shaking heads, except—How could I have missed this?—they were all looking down at their cellphones, as though they might have had the answers to my questions.

Maybe they did.

I recalled a recent survey about teenage immersion in social media, youngsters between the ages of 13 and 17. Ninety percent of them rely on YouTube every day; 63 percent on TikTok; 61 percent on Instagram and 55 percent on Snapchat.

Teenagers live with social media, which has become their principal means of communication, their way of learning about the world they inhabit, like their parents, who have also come to depend on it, although not as wholeheartedly. Their numbers are lower but still meaningful.

Obviously, I needed yet another approach. I decided to tell a story. Don Hewitt, the founding director of CBS’s “60 Minutes” once told me that everyone, no matter how young or old, liked a good story; and Murrow was a very good story.

I had met him in May 1957 in a most unusual way. I was a graduate student at Harvard, deep into PhD research in Russian history, most days tucked away in a small carrel at Widener Library. One Monday morning, an elderly librarian interrupted my studies. “Marvin,” she whispered, “there’s a call for you, a man who says he’s Edward R. Murrow.”

“Hang up on him,” I shrugged. “Probably a quack. Edward R. Murrow is not calling me.” Crazy idea, I thought.

As it happened, Murrow was my hero at the time, a journalist so lofty in my imagination I could not believe he would be calling me. At 7:45 p.m., Monday through Friday, nothing could distract me from listening to CBS’s “Edward R. Murrow with the News.” He was my contact with the world, strong, reliable, accurate.

Late that afternoon, the librarian returned. “He just called again,” she whispered nervously. “It’s the same man. I think you ought to talk to him.”

I began to have second thoughts. Perhaps it was Murrow, responding to a story I had written about Soviet youth, which had appeared the day before in The New York Times Magazine. Maybe he’d read it.

I picked up the phone. “Hello?” I said.

“This is Ed Murrow. I’m sorry to bother you.”

The instant I heard his voice, I realized what a fool I had been. It was Murrow, and he was calling me twice in one day.

I erupted with apology. “I am so sorry, sir. Please forgive me. I’m sorry.”

“No problem,” he replied. “I read your piece in the Times yesterday, really good piece, and I wanted to talk to you about it.”

“Yes, sure. Thank you. Wow. Yes, of course.” My words tumbled out in no order. I was overwhelmed.

Murrow, though, quickly got to the point. “Could you possibly get to my office tomorrow morning?”

“Yes, sure, where?”

“New York, 485 Madison Avenue, 9 o’clock. Ok?”

“Yes, sir. I’ll be there.”

Thus began a relationship that inspired my career as a broadcast journalist.

That first meeting was penciled in for 30 minutes. “He’s a very busy man,” his secretary warned. The meeting lasted for more than three hours. Like a curious graduate student, Murrow asked dozens of questions about Soviet youth: their families, parents, jobs, religion, sex, patriotism, war, Stalin and the new leader, Khrushchev (I noticed Murrow took notes); and I, like a young professor hustling for tenure, tried answering every question. It was a seminar like no other.

When his secretary interrupted shortly after noon, mentioning Murrow was already late for a lunch, the famed broadcaster slowly stood up, smiled and, with an arm around my shoulder, asked, “How would you like to join CBS?” It might have taken a second or two before I answered, “Yes, sir, of course, yes, I’d be delighted.” For me, it was “Bye, bye scholarship; hello journalism!”

I had been a sports reporter for my high school and college newspapers, but never before a reporter on salary for a professional news organization. Murrow thought CBS needed a Moscow correspondent who spoke Russian and understood the complicated flow of Russian history and politics. He helped put me on a fast track, from local writer to network reporter to foreign correspondent, and, in May 1960, CBS took a chance and assigned me to Moscow. It was a gamble that came adorned with a professional dilemma Murrow himself created.

Less than a year later, after he had left CBS to join the incoming Kennedy administration as head of the United States Information Agency, he called one day and, unintentionally, placed before me a flattering but incredibly difficult proposition: Would I accept a new job as Murrow’s personal adviser on US relations with the communist world?

If I were not so deeply committed to my job as CBS’s Moscow correspondent, I would have jumped at the opportunity to help Murrow during the Cold War. He was still my hero. How could I respond in any way other than “Yes, sir, when do I start?” But after a period of intense introspection, I came to a very different decision. I would stay in Moscow for CBS. I wanted to continue to be a journalist, enjoying the freedom, challenge and satisfaction of informing the American people about what was happening in Russia. Murrow also helped, saying that if he were in my position, he’d have reached the same conclusion. He was always gracious.

He was also an extraordinary journalist, the most gifted broadcaster of his era, inventing radio news while reporting courageously on the rise of Hitler’s fascism in Germany in the 1930s, the Luftwaffe’s blitzkrieg of London in the 1940s and the spread of McCarthyite terror and fear through the United States in the 1950s. Murrow felt the need to cover the junior senator from Wisconsin not just as a compelling news story but, in his judgment, as a serious threat to American democracy.

When he returned to New York after covering World War II, Murrow believed that if Germany, a highly civilized country in central Europe, could produce such a raw, cruel, ugly evil as Hitler’s fascism, then so too could other civilized nations, including the United States, produce their own iterations of evil. And were that to happen, it would become, as he put it, the “responsibility” of every “citizen” to oppose that evil. For Murrow, McCarthyism was precisely such an evil force, and it had to be confronted.

The Cold War set the ideological framework for the famous Murrow/McCarthy confrontation on network television. The senator was riding high, conducting a personal crusade against the “communist threat” in Hollywood, the State Department and the US Army. He charged, without evidence, that such high-ranking officials as General George C. Marshall and Secretary of State Dean Acheson were somehow engaged in helping the communists in “subversive, anti-American activities.” In this way, he spread a strange fear through the country that stifled dissent and discouraged criticism.

By early 1954, McCarthy had become so powerful a national figure that, according to a Gallop poll, 46 percent of the American people “approved” of his anti-communist campaign. Among elected officials, only President Dwight D. Eisenhower enjoyed a higher approval rating, but not by much.

Murrow felt he had to exploit the power that was his, the pervasive power of radio and television, to stop McCarthyism. Teamed with the legendary producer Fred Friendly, he dug deeply into the McCarthy threat to democracy. He covered McCarthy’s hearings, speeches and interviews, in the process producing a run of revealing broadcasts that focused on the senator’s lies, exaggerations and distortions.

Finally, on March 9, 1954, Murrow broadcast a devastating point-by-point dissection of McCarthy’s rhetoric and actions. McCarthy had crossed a line of decency that had to be exposed. “We will not be driven by fear into an age of unreason,” Murrow declared, staring directly into the camera. “The actions of the junior senator from Wisconsin have caused alarm and dismay amongst our allies abroad and given considerable aid and comfort to our enemies.”

He closed his memorable broadcast by quoting Shakespeare. “Cassius was right,” he proclaimed. “The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars but in ourselves.” Murrow was obviously trying to wake up a frightened people.

There was a rule at CBS that reporters should stick to the facts, no editorials allowed. But in this special broadcast, Murrow was clearly presenting his own opinions, and doing so forcefully. Apparently, few other reporters and writers had the courage in those days to take on the formidable McCarthy assault on democracy. There were exceptions, of course, led by Dorothy Thompson, her husband the Nobel Prize-winning author Sinclair Lewis and columnist Drew Pearson.

McCarthy believed that the popularity of his anti-communist hysteria was untouchable, skyrocketing from one Gallop poll to the next. But he was wrong. Murrow’s broadcast put the skids under his nationwide crusade. The response was overwhelmingly positive. McCarthy’s approval rating dropped dramatically, from 46 to 32 percent, and it never recovered. The Army-McCarthy hearings, which followed a few months later, added to McCarthy’s accelerating decline. Republican senators, who had been frozen into fearful silence, never daring with few exceptions to criticize McCarthy, suddenly found their voices. They stripped him of his power to chair investigating committees, and voted their disapproval of his actions, although in very gentle language. Still, for the GOP, these were bold steps, and McCarthy, as both a politician and a movement, faded into oblivion.

By this time, the students back in the classroom were no longer silent or stoic in manner. They were alive with a new excitement, hands were raised, questions flowed, one after another. There wasn’t enough time to answer all of them, but one demanded an immediate reply.

What made Murrow feel he had to take on McCarthy?

The answer was his sense of patriotism. When he believed American democracy was in danger, he felt he had to act.

I told the students that in my conversations with Murrow, it was clear he was reluctant to talk about McCarthyism (“Let the broadcast speak for itself,” he’d say), but he had no hesitation discussing his definition of American democracy. Two pillars supported this “precious” concept, he’d explain, while stressing that words, such as “democracy” and “freedom,” have value only to the extent that people vest in them a special meaning. Otherwise, they are just words.

One pillar was what Murrow called the “sanctity of the courts,” the other “freedom of the press.” So long as both remained strong, democracy itself would, in Murrow’s view, also remain vital, relevant, worthy. But if either pillar were to become wobbly, as now seemed to be the case with both, then democracy itself would also wobble, weaken—and ultimately collapse.

In the Broadway play, a sparkling redo of the 2005 movie by the same name (also co-starring Clooney, who directed), the focus is on Murrow’s successful fight against McCarthyism in the 1950s. But everyone in the audience knew that another version of Murrow’s fight was now hovering over American democracy, namely, President Donald Trump’s assault on the free press.

He apparently believes that he is Editor-in-Chief of American journalism. He sets the rules. Journalists should write only favorable stories about him. They should not critique him or ask embarrassing questions. He reserves for himself the unquestioned right to sue journalists who violate his rules. He has already sued ABC News and CBS News. He has trimmed the venerable sails of “60 Minutes” and set the stage for ending Steven Colbert’s “The Late Show.” He has also sued The Wall Street Journal for publishing a story and photo linking Trump to the disgraced Jeffrey Epstein.

Before the students, I raised what I hoped would be a compelling question: Is there a Murrow in the world of contemporary journalism, dominated by social media, who would take on the Trump challenge and emerge as a hero of truth over lies, fact over falsehood? An awkward silence enveloped the classroom. No one could come up with a candidate, neither the honor students, nor their teacher, nor the visiting journalist. There was no Murrow in social media, nor in any network. He worked in another era of American history.

That being the case, might it suggest that journalism, as currently practiced in the United States, has trouble covering a chief executive who is accumulating unprecedented power, and that as a result the US finds itself drifting toward an authoritarian form of government? At least in that one Boston classroom, the answer was unmistakably “Yes.”

Marvin Kalb, Murrow professor emeritus at Harvard University, is a former network correspondent. His roles included chief diplomatic correspondent and Moscow bureau chief for CBS, and anchor of NBC’s “Meet the Press.” He went on to become founding director of Harvard University’s Joan Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy, and has published 18 books, including his most recent, A Different Russia: Khrushchev and Kennedy on a Collision Course.