‘No need for a world without us’

Whatever happened to North Korea?

Reviewed in this article:

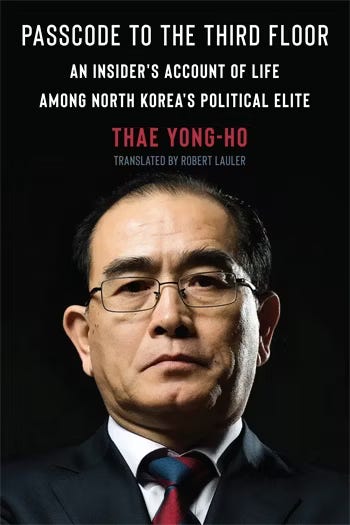

Passcode to the Third Floor:

An Insider’s Account of Life Among North Korea’s Political Elite

Columbia University Press, April 2024

by Thae Yong-ho

Robert Lauler, trans.

Speaking in a film produced by the notorious Kremlin propagandist Vladimir Solovyov in 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin discusses the possibility of a nuclear apocalypse. “For humanity, it would be a global catastrophe,” he muses. “But I—as a citizen of Russia and head of the Russian state—would like to ask one question: What good to us is a world without Russia?”

Against the backdrop of Putin’s religion-tinged nationalism—he told a 2018 conference that in the event of such a disaster, Russians would go to paradise as martyrs while “the aggressors would just croak…without time even to repent”—the president’s comments sounded more ominous than even the saber-rattling of the Cold War.

Such utterances by the leader of a nuclear power were echoed in an earlier episode in North Korea. During a meeting with military personnel in 1991, then-leader Kim Il-sung—founder of the Stalinist state—asked what Pyongyang should do if South Korea and the United States were to attack. Kim’s son and soon-to-be successor, Kim Jong-il, declared that the North would respond by destroying the world. That was just the kind of answer the elder Kim wanted to hear: There’s no need for a world without us.

The anecdote is related in Passcode to the Third Floor: An Insider’s Account of Life Among North Korea’s Political Elite (2024), a new translation of a memoir by Thae Yong-ho, a former senior North Korean diplomat who defected in 2016. As Putin’s Russia becomes inexorably more repressive, with the specter of authoritarianism rising around the globe, it provides an instructive look at the workings of perhaps the most extreme example.

Originally published in 2018, Thae’s account is a substantial volume that paints a broad but nuanced picture of the North’s diplomacy, politics, society and history spanning 50 years. He explores the development of the country’s nuclear program, concluding it will never be abandoned. That view was reinforced in September when current leader Kim Jong-un declared that Pyongyang was open to talks with the United States only if Washington were to stop trying to denuclearize North Korea.

All sorts of stakes, including nuclear ones, have been raised by the wars in the Middle East and Ukraine; North Korea has been directly involved in the latter. Last year, it sent at least 10,000 troops to support Russia’s war effort, although Pyongyang’s active support of Russian aggression dates back to shortly after the full-scale invasion in February 2022.

As of last April, the North was supplying half the munitions Russia needs at the front, news media reported, having earned more than $20 billion from its involvement, an open secret recently confirmed. This troubling mésalliance has prompted another bout of questioning about North Korea’s intentions, resources, prospects and general existence. Passcode to the Third Floor has a lot to say about that.

Before his defection, Thae was privy to much of what the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, North Korea’s formal name, has done internationally since the 1990s. Today, he’s a politician in the South whose main goal is reunification. He says his book is an attempt to give “a correct understanding of the current state of North Korean society.”

The book’s developing tone of disappointment reinforces its impression of veracity and the author’s powers of observation. Initially, Thae was no internal enemy of the regime, waiting for a chance to defect. Born in 1962, he says his youth coincided with the best time in North Korea’s history—the mid-’60s to the mid-’70s—when the standard of living was roughly on par with the largely impoverished South’s. The socialist state appeared to be working, fostering confidence, loyalty and pride. Thae devoured politically correct Soviet novels; his family adhered to the party line.

In 1976, he took a rare opportunity to study in China, where he was photographed with Kim Il-sung during a visit. Later, he attended Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies, became proficient in English and joined the ruling Workers’ Party of Korea. He married into a family that all-but “held the entire North Korean armed forces in their hands”: His father-in-law was a general, the nephew of a comrade-in-arms of Kim Il-sung and the cousin of senior leaders in both the air force and navy. Thae built a stellar career at the Foreign Affairs Ministry that culminated in his appointment in 2006 as deputy ambassador to the United Kingdom.

Some of Thae’s described professional successes involved helping establish relations with the West and procuring food aid that was partly used to feed the military instead of malnourished children. He was able to put a stop to mass games training in preparation for Kim Jong-il’s birthday, saving thousands of children from having to practice tumbling on concrete through the winter—the “proudest thing” he did while posted in Britain: Shamed by a British official who abhorred such displays of collectivism, Thae sent Pyongyang a telegram suggesting it would be bad for North Korea’s image. The message found its way to Kim Jong-il.

In 2002, Thae helped set up the first Western media bureau in Pyongyang for The Associated Press Television News. He arranged North Korea’s participation in the London Paralympic Games in 2012 and made it possible for a troupe of disabled teens to put on unusually apolitical performances in Britain and France in 2015 that included dances from Snow White and the Seven Dwarves and songs from Phantom of the Opera.

Thae doesn’t appear to sugarcoat his narrative, however. If your ambassador has been ordered to extort $1 billion from Israel in exchange for not exporting missile technology to the Middle East in 1999 and wants you to interpret, you interpret. If the German embassy in Pyongyang displays an EU text criticizing the DRPK for shelling South Korea’s Yeonpyeong Island in 2011, you find a way to make them take it down. And if a beauty salon in London irreverently displays a picture of Kim Jong-un in 2014 (“Bad Hair Day? 15 percent off for male customers!”), you threaten the owner.

The recurring absurdity of life in North Korea would be amusing if it weren’t so sad. A Catholic woman who was informed she would be sent to the Vatican to prove that there are, in fact, religious people in North Korea—Kim Il-sung wanted to invite Pope John Paul II to visit—praised the Lord only to be reminded that God had nothing to do with it: She was to act in the interests of the revolution. Elsewhere, Thae seems to paint a sympathetic image of an amusingly dysfunctional country where nothing works yet nothing is impossible. But it is overshadowed by his overall depiction of a “society of oppression that should never have existed.”

Thae writes a lot about the purges that define the country’s political culture. He explains the role of North Korea’s political heart of darkness—the so-called Third Floor Secretariat, a powerful and secretive agency within the Party’s Central Committee office complex—in the system “that turned Kim Jong-il into a god.” North Korean government departments don’t communicate with each other, reporting directly to the Supreme Leader. The secretariat makes sure it stays that way, providing close support to the chief; in short, it ties the system together.

Over time, Thae’s diplomatic career becomes increasingly overshadowed by his moral sense, echoing what the sociologist Erwing Goffman writes about “total institutions” such as prisons and concentration camps” conditioning the beliefs of their inmates.

A revelatory moment came in 2015, when Thae was charged with escorting Kim Jong-un’s brother to an Eric Clapton concert in London. It dawned on him that he had turned into “a prisoner taking care of a prison warden.” He finally decided to defect after he was ordered to send his older son, whom he had managed to bring to London, back to Pyongyang.

Today, Thae is a vocal advocate of Korean reunification who argues that Kim Jong-un is becoming a “greater and greater failure.” His charisma is diminishing, Thae says; elites are wary of him; his fear-based politics are increasingly less effective. Thae argues that the population’s tolerance for the regime’s lies is dwindling: “When all North Koreans know the truth and reach a consensus, the Kim Jong-un regime will collapse with barely a whimper.”

Wishful thinking, perhaps, but Thae’s expertise shouldn’t be discounted. One matter is clear: The North Korean nuclear program remains a hard, disturbing reality. At best, it may simply enable Kim to enjoy the idea that he’s a global leader to be reckoned with. But it could also be used the way Putin is now exploiting Russia’s nuclear arsenal—to enable conventional war by threatening global annihilation. After all, North Korea as well as South Korea wants to unify the peninsula.

Dmitry Kharitonov is a London-based literary critic, translator and editor. His main areas of interest are American and Russian studies.