On The New Yorker

Harold Ross's gamble, 100 years on.

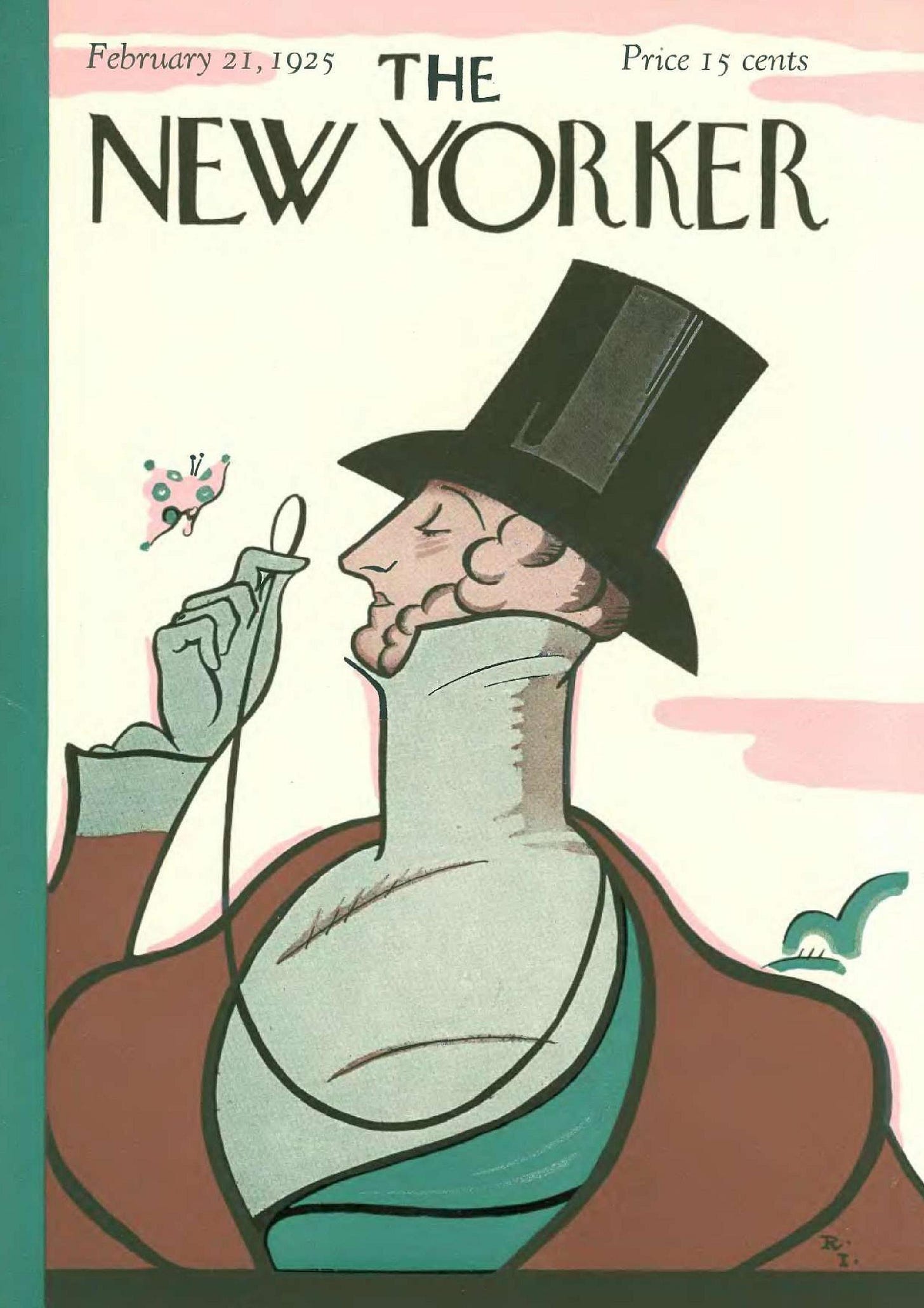

In our digital age, when radical change seems to be the norm, it’s remarkable The New Yorker magazine is celebrating its 100th anniversary this year. Cars can now drive themselves, computers manufacture emotions and civilians routinely travel into space. But this periodical, which first hit the newsstands on February 21, 1925, is still arriving on our doorsteps every week (assuming you still subscribe to the print edition). What’s the secret? It goes back to the beginning and the founding editor, Harold Ross.

Print magazines were omnipresent and lucrative businesses in the 1920s. There was a rag for everything—fashion, movies, detective stories, sports, comics, travel—and in the days before television, reading The Saturday Evening Post was what you did on Saturday night. Subscribers numbered in the millions and fortunes were made on the strength of new niches that could find a place among the countless offerings at the newsstand (now a vanishing enterprise like magazines).

A high school dropout from a mining town in Colorado named Harold Ross envisioned such a niche for a sophisticated humor magazine that would not be “for the lady in Dubuque,” as he wrote in his prospectus. A reporter and war veteran in his early 30s, he was qualified despite his lack of formal education, with a rough-and-ready background in the West and experience on various newspapers, including in Salt Lake City and San Francisco, where payment for a story was sometimes doled out in booze.

Ross’s ambition and boundless energy notwithstanding, his venture did not start well. Within the first few months of publication, sales were so poor he (and his main financial backer Raoul Fleishmann of Fleishmann Yeast fame) was thinking of calling it quits. But he stuck with it. A founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, he hired the inestimable talents of James Thurber and E. B. White, the fiction editor Katherine Angell, cartoonists Peter Arno and Helen Hokinson and others. With rising subscription rates, advertisers eventually flocked to The New Yorker’s pages and revenue grew steadily throughout the 1930s and 1940s.

The magazine’s understated, measured tone, matched with subtle wit, gave the reader a portal to understanding issues of the day, even if they were sometimes risqué. Thurber’s cartoons lampooning the battle of the sexes in the 1920s (where women loomed physically larger than men), for instance, reflected the changing mores of the New Woman and supposed male feelings of inadequacy. Without such touches of humor together with a less serious, analytic tone, readers might have shied away from difficult subject matters.

When times changed during World War II, The New Yorker provided readers a reflective escape from newspaper banner headlines about the fighting. Although the magazine covered topics about the conflict, it did so in its quintessentially detached, thoughtful style—seemingly dispassionate but above the fray. Readers found it a welcome relief. But when Ross published John Hersey’s article about Hiroshima shortly after the atomic bomb was dropped, he knew it would be jarring to include cartoons in the issue, so he nixed them that one time.

He went on to hire a new wave of journalists who helped maintain the level of seriousness, including Joseph Mitchell, Joseph Liebling, Janet Flanner and Lillian Ross. He was also a poster boy for workaholics, keeping long hours at the office and home, obsessing over every detail of every issue. No poorly placed comma or unfunny cartoon caption was safe from scrutiny and sometimes wrath. “I would love to hear the sound of a tipper-tapper!” he would howl down the hallways of the magazine’s offices when the noise of typewriters abated.

By the late 1940s, Ross was literally working himself to death and became seriously ill. A heavy smoker, he developed bronchial carcinoma and died in 1951 at the age of 59 from heart failure. His successors, including William Shawn, Robert Gottlieb, Tina Brown and the current editor David Remnick (now in his 25th year) would carry the mantle of his legacy, achieving continued critical acclaim and keeping devoted readers eager for the latest issue.

I was one of them and still am. Like many young readers, I was first drawn to the magazine’s cartoons (as a budding cartoonist myself). During 1980s in college, I grew to appreciate the magazine’s colorful history and was taken with James Thurber’s biography of Ross I discovered in the library stacks, The Years with Ross.

Although many of the magazine’s editors disliked the book when it came out in 1957, believing Thurber had made Ross into a bumbling caricature rather than a serious editor, the portrait made for great copy. It inspired me years later (in 2000) to produce and direct a documentary about Ross and the magazine’s early days, “Top Hat and Tales: Harold Ross and the Making of The New Yorker” (narrated by Stanley Tucci), which drew on interviews with many legendary writers, editors and cartoonists including Roger Angell, Gardner Botsford, Lillian Ross, Brendan Gill, Frank Modell, Andy Logan, Emily Hahn and Mary D. Kierstead.

I had been fortunate to come to know many of those figures personally, and in some cases, develop long-standing relationships, especially with Angell. We would meet for lunch once a week for 25 years at an artists’ club in Manhattan. Often, although not routinely, the conversation would turn to the magazine where he regularly worked for 70 years (he died in 2022 at the age of 101). Many of his stories centered on Ross and those early days, and I acquired from Angell and other staffers an increasingly nuanced sense of Ross as a man of contradictions rather than the coarse hayseed others portrayed. He emerged as a very shrewd man with a keen sense of what makes a great editor.

I had already made a film several years earlier about Thurber, shown on PBS (George Plimpton narrating). One of the challenges was bringing Ross to life without the benefit of many photo stills or footage of the Great Man himself. Despite his success, Ross was not a public figure and shunned the spotlight, although he was often seen at clubs around town. The only photos I had were mostly publicity shots. Fortunately, Ross’s daughter, Patricia Ross Honcoop—on whom Ross had doted, and who was living at the time on a commune in Bolivia—shared a treasure trove of scrapbook material with me, including many photographs. They were just what I needed: casual, candid and revealing.

When I screened the film at festivals, I was surprised to hear how much many viewers said they had learned about the “lovable old volcano,” as one of his obituaries put it. A century on from his magazine’s founding, its importance to American intellectual life can’t be overstated.

Adam Van Doren is an award-winning author, artist and filmmaker; his books include An Artist in Venice, The House Tells the Story: Homes of the American Presidents, and In the Founders’ Footsteps: Landmarks of the American Revolution. He teaches painting at Yale University.