‘Prolonging the life of this bizarre case’

Persistent echoes of the Scopes ‘monkey trial.'

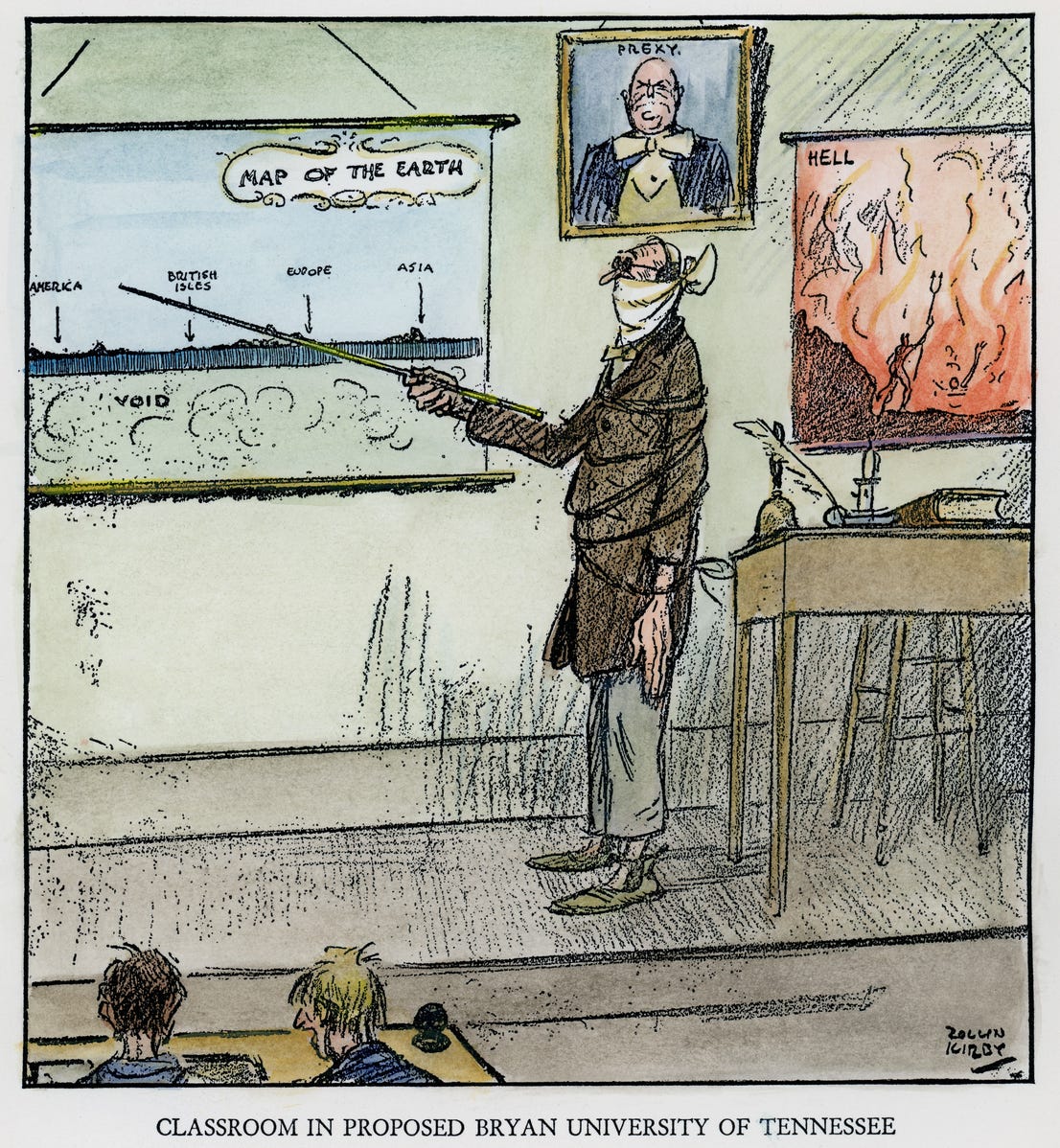

In July 1925, the trial of a 24-year-old high school substitute teacher named John Scopes got under way in a steamy courthouse in Dayton, Tennessee. As the Institute of Current World Affairs marks the centenary of its founding this year, we’re looking back on other events 100 years ago that continue to resonate in 2025—and perhaps none meet that description as well as the so-called Scopes “monkey trial,” a demonstration trial brought by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) to test Tennessee’s Butler Act. That law, similar to many others adopted or under consideration in other US states, made it unlawful “to teach any theory that denies the story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man descended from a lower order of animals.”

The proceedings—to mention a particularly entrepreneurial twist—were instigated in Dayton by canny local businesspeople who envisioned them as a culture-war publicity stunt to jolt the town’s crumbling, mining-based economy. Dayton constructed a new telegraph office and an airstrip to accommodate the 100-plus reporters who flocked there, and trial was the first ever to be broadcast live on radio across the United States. (One of the first to approach Scopes about participating in the trial was a young local lawyer named Sue Hicks, thought to have been the inspiration for the song that became one of Johnny Cash’s biggest hits, “A Boy Named Sue,” written by Shel Silverstein.)

The prosecution’s side was argued by the progressive populist and three-time Democratic Party presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan. Clarence Darrow—the brilliant civil libertarian some consider the 20th century’s best lawyer—argued for the defense. At the close, the jury returned its verdict after deliberating for just 10 minutes, finding Scopes guilty of violating the Butler Act. However, the Tennessee State Supreme Court overturned the decision on a technicality soon after, urging prosecutors to drop the matter because there was “nothing to be gained by prolonging the life of this bizarre case.”

The court’s opinion notwithstanding, the question of whether schools should be allowed to teach evolution helped expose a yawning divide in public opinion. Political developments at the time uncannily mirror today’s: With conservatives in ascendence, Congress had passed strict immigration quotas, blaming foreign influences for undermining “traditional” values. Isolationism was mounting, intellectualism under attack and the Ku Klux Klan was reaching the height of its power, manifested by a Klan parade down Washington DC’s Pennsylvania Avenue in August 1925 of some 30,000 marchers, with 150,000 spectators looking on.

This year’s numerous remembrances of the eight-day “trial of the century”—held less than a decade before the trial in the case of the Charles Lindberg baby kidnapping usurped the title—testifies to its continuing importance. The role of the state in education, the separation of church and state, the role of courts in adjudicating “culture wars,” the latent public distrust of expertise, the defense of “traditional” values in the face of new knowledge and evolving cultural mores and other issues continue to be third-rail matters in the United States and other societies around the globe.

An NPR article summarizes the proceedings as “one of the first highly publicized battles in the US between traditionalist and modernist values surrounding science, religion and education—a conflict that continues to this day.”

“The trial left a lasting impression on these debates,” it adds, citing experts pointing to today’s contretemps over abortion laws, posting the Ten Commandments in public places, prayer in schools and whether parents may excuse their children from school lessons touching on LGBTQ+ issues as direct descendants of the disputes at the heart of the Scopes trial.

The Christian Science Monitor writes that media coverage of the Scopes trial “mocked traditional religious views” and “the rural areas where many fundamentalists lived.”

“The term ‘fundamentalist’ began to be a smear,” the article says. Over the ensuring decades, the chastened fundamentalist movement rebranded itself as “evangelical” and reemerged as a political powerhouse “rooting itself in significant parts of national culture.”

And the historian Michael Kazin, writing in The New York Times in another piece linked to the trial’s centenary, also argues that it helped break the traditional alliance between the rural poor and the Democratic Party, partly by exposing the revulsion urban liberals “felt toward people they deemed dogmatic and uneducated.” Rural fundamentalists had overwhelmingly supported William Jennings Bryan in his presidential bids on the Democratic ticket. John Butler, the Tennessee state representative who authored the Butler Act, was also a Democrat.

“Throughout his career, [Bryan] had denounced corporate power and big financiers like J.P. Morgan while championing crop subsidies, labor unions, a ban on large donations to campaigns and higher income taxes on the rich,” Kazin writes. “That may point a path forward for Democrats grappling with how to reach rural voters today.”

The issue of teaching evolution in schools continues to crop up regularly despite the overwhelming scientific consensus supporting Charles Darwin’s theories of evolutionary biology, as a summary by the Associated Press shows. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court struck down an Arkansas law banning the teaching that “mankind ascended or descended from a lower order of animals.” In 2005, a federal court ruled that a district in Pennsylvania couldn’t teach the evangelical-inspired theory of “intelligent design,” dismissing it as “a religious view, a mere relabeling of creationism, and not a scientific theory.”

Fast forward to today, when the dynamic has reversed: A new school curriculum in Texas asks children to memorize the order in which the Bible says God created the universe. Earlier this month, Education Secretary Linda McMahon was asked in testimony before a House committee whether “parents should have the ability to opt their child out of a unit on evolution.”

“Yes,” she said. Parents should make such decisions based on “their own ideals…their own religious backgrounds.”

Robert Coalson is a retired journalist who spent more than 20 years reporting on Russia, the former Soviet Union, and the former Soviet bloc for Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.