‘This is not the end of moral universalism’

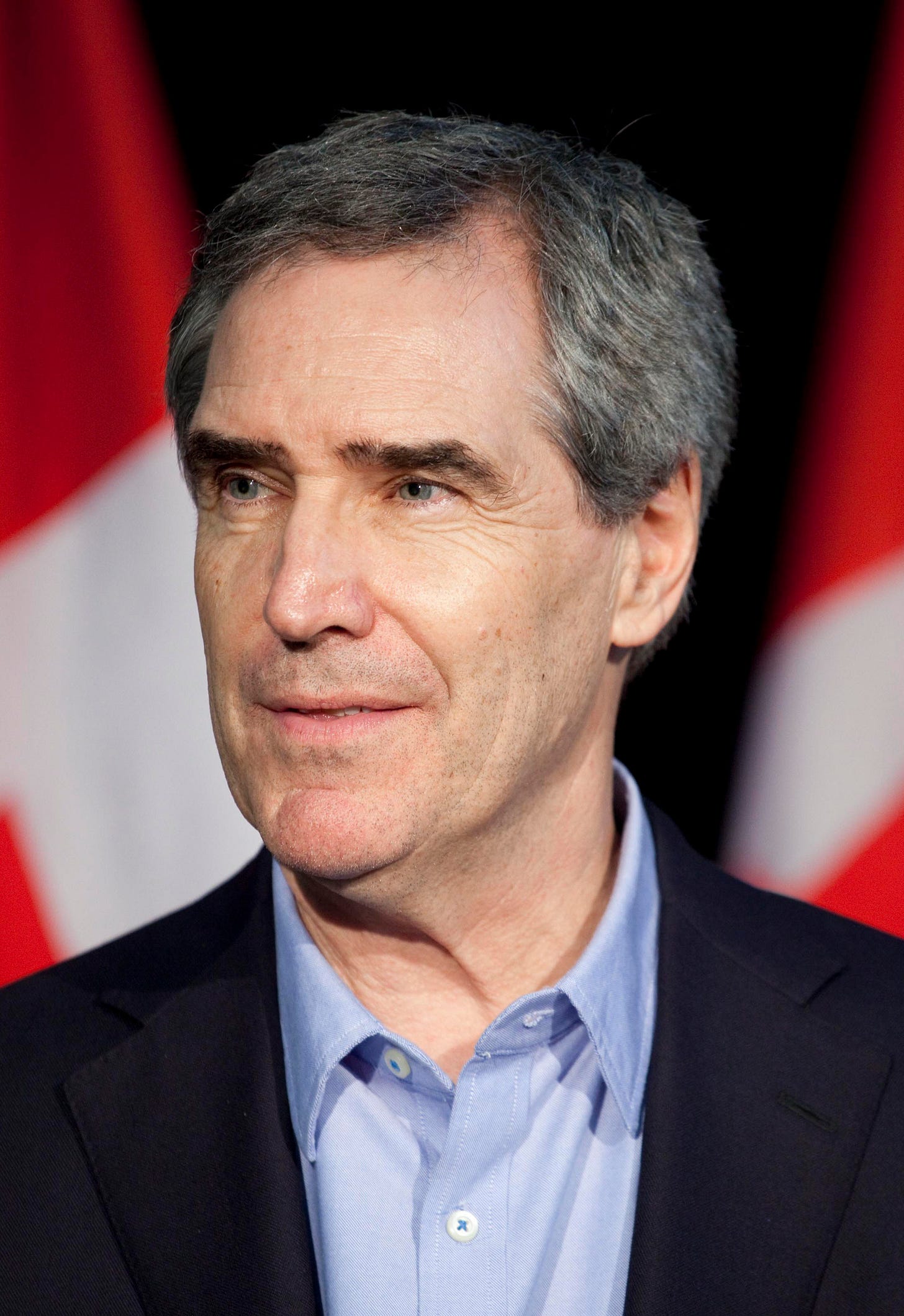

A conversation with Michael Ignatieff

US President Donald Trump’s second administration of has dramatically changed the geopolitical climate, kicking the ascendence of authoritarian populism into high gear around the globe. What’s behind it and what should we be doing? Compass’s Robert Coalson asked the historian and former Canadian opposition leader Michael Ignatieff.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Robert Coalson: I’d like to begin with Canada’s relations with the United States. In a recent interview with CNN, you said the latest election was the strongest showing of nationalism in your lifetime but warned that Canadians now need to brace themselves for the “painful reality” of “this new world.” Could you elaborate?

Michael Ignatieff: In the North Atlantic world, we took for granted that we benefited from the more-or-less benign hegemony of the American Imperium. The American Imperium was not benign in Southeast Asia. It was not benign in Iraq. It was not benign in Latin America. And it was not benign in Iran. But for North America, for Canada particularly, and for Western Europe, and also to some extent, for Eastern Europe, it was.

It appeared to be the condition of our economic security and our geostrategic security. And we were vaguely aware that we were free-riders, or close to free-riders, on these global public goods provided by the empire, and now suddenly—I think, largely because of American domestic discontent with the way their democracy is functioning and the way their economy is functioning—a leader has emerged who has ridden to power on that discontent and is mandated by a democratic public to end the free riding, restore manufacturing and stop regarding allies as friends and regard them as competitors and adversaries. In other words, discard the imperial mindset of 1945 and instead embrace a mindset shaped by the very different conditions of 2025.

It’s no accident that Canada has been on the front line of that since we’re the most trade-exposed and trade-dependent economy of any of America’s allies. So that means we have an unusual and particular challenge. It’s not merely that we export 80 percent of our production to the United States. It’s that we are tied into supply chains with the United States that are the condition of the survival of whole manufacturing sectors, like automobiles.

So suddenly, we’re in a world where we have to rethink the basic pipework of our economy, which the pipework is mostly north-south and cross-border. The electricity grids run north-south. The pipelines run north-south. The manufacturing supply chains work north-south. And suddenly we’re looking at, how do we create an economy that works east-west? We have substantial internal trade barriers. We have very weak connectors between the various economic centers of the country. They’re much stronger north-south.

So suddenly, we’re in a very concrete, real way in a new economic space. And we’re also in a new space in terms of having to stump up much more for our defense than we ever conceived of having to do before. So that’s the challenge.

I think Canadians were at first stunned, then furious and they felt betrayed by this sudden change of American policy and by what accompanied it, which was: “You really shouldn't exist. You’d be much better off with us. We don’t need anything from you. You really make no sense as a political system. Total economic integration should be followed by total political integration.”

And Canadians thought: “We like economic integration, but we absolutely hate political integration, don’t want anything to do with it.” So it has been a moment of catalytic self-discovery for Canadians, discovering that we were willing to have economic integration but didn’t want political integration, and now we’re suddenly facing up to the increasingly large economic price that we’re going to have to pay for political independence. And that’s a shock.

It has awakened a tremendous outpouring of nationalist feeling, and no Canadian politician of whatever party can afford to ignore the strength of this feeling. So the calculation that [Prime Minister Mark] Carney or any prime minister would have made is: “We are going to be tough.” So we’re one of the few countries that slapped retaliatory tariffs on the United States. Most other countries are holding off retaliatory tariffs, with the exception of China, because they think: “Let’s play this cool. Let’s play it smart. Let’s make nice.” The Canadian judgment, very unusual for us, is it doesn’t pay to make nice. And so the prime minister went into the Oval Office and was told once again that you would really be better off if you didn't exist. And he said, “I’m sorry; we’re not for sale.”

That was the minimum he had to say. But the reality is that he didn’t come out with any promise to reduce the tariffs. So we’re in a very difficult, long-term struggle which is essentially about our survival as a separate, independent, national state. And so it’s existential in that way, and I think it’ll be a very considerable test of Carney because there’s a limit to how much a country next door to the largest market in the world can diversify; there’s a limit to how much it can strengthen its sinews of national economic independence. It’s going to be tough but politically, I don’t think there’s any other way than defiant counteraction and that’s why I put everything the way I did. And I think that’s what most Canadians are feeling.

Coalson: It sounds like average Canadians are going to have to make a lot of sacrifice and put in a lot of effort. Is this nationalist feeling that you’re seeing strong enough to see them through that?

Ignatieff: Well, that’s the political question of them all. It’s not just what individual Canadians are prepared to sacrifice in terms of stress on their standard of living. Canada is an extremely rich country, and it’s got the tax base to soften the blow. The question is how long it goes on and how long it will take an economy that’s oriented north-south to reorient east-west. My sense of the political problem is that this is a 10-year project, and very few political systems nowadays can sustain a 10-year project. It’s very difficult because governments come and go and, as you say, people get tired of the sacrifice and they begin to feel remorse for their nationalist fervor and begin to want to dial it back and make a deal and get back to a quieter life.

But I’m not sure there is a quieter life. Because I’m not sure that Trump is just a passing phenomenon. I think there’s a tendency to wait him out, to think, “Well, let’s wait until the midterms. Let’s wait till 2028.” But when they get [US Vice President] JD Vance [as the next president]… We may, alternatively, get a Democratic administration that is picking up the same messages that Trump picked up, namely, “We are tired of the burdens of empire.”

I think that’s the big story. It’s not simply a rampaging right-wing coup led by some ideologically enraged right-wingers. What’s going on is a democratic revolt against the cost of empire, skillfully exploited, managed by some ideological figures. But the real problem is the depth of the American disillusion with the cost of being a global leader. I think that’s why it’s not going away, and that’s why every subsequent administration will ask, “What’s in it for us?” Trump has been the first to ask this so directly but he won’t be the last. That’s why I think we’re facing a permanent challenge.

Coalson: It sounds like you view the populist movement in the United States as somehow qualitatively different from populist movements in other countries around the world, like Hungary.

Ignatieff: There isn’t any doubt that there’s a kind of populist international. There’s a right-wing, conservative international. Republican figures from the United States have gone to make pilgrimages to talk to [Prime Minister Viktor] Orban in Hungary, and Mr. Orban has given speeches that have helped inspire [Germany’s] AfD, [Marine] Le Pen [in France] and [Geert] Wilders [in the Netherlands]. So there are a lot of affiliations.

But what is distinctive about the United States is that this is a democratic revolt against the cost of empire in the one country that can claim to be an imperial power, and that therefore distinguishes American populism from anything in the other countries, although they have similar grace notes. I mean the similar hostility to gays, similar hostility to a kind of liberal cosmopolitanism, liberal equality and all that stuff. They are similar themes and notes, but what’s distinctive in the United States is just a challenging of America’s global role and of the costs of being a provider of global public goods.

I think that’s, in turn, an expression of something that was a real feature of American foreign policy after 1945, based on a very powerful [reaction against] a foreign policy elite in Washington and New York that kept renewing itself. You know, I taught at Harvard and so I saw how elite institutions reproduce this foreign policy elite, sometimes affectionately and not so affectionately, called the Blob. And it’s a revolt against the Blob: “You people in your think-tanks and universities and this and that sent our kids off to fight these bloody wars, and we kept losing these wars.” The 50th anniversary of the Vietnam War is a very pungent reminder of just what price ordinary Americans paid for the anti-communist consensus of the Blob in the 1960s. And since I marched against that war as a young student, I remember how angry we were at the “best and the brightest,” and how they led us all astray. Some of that resurfaced again in Iraq, and some of it resurfaced in the precipitous withdrawal from Afghanistan. I think that’s the big story. And since none of the other populist revolts are in countries with imperial roles, I think that’s what makes American populism distinctive.

Coalson: An interesting take on this argues that in the United States and maybe in France as well, democracy has been more than a system of government, but also a key part of national identity, of national ideology. I wonder if you agree with that, especially with regard to the United States, and whether you’re surprised at how willingly American voters have seemed to disregard the threats to democracy and thrown off this national identity.

Ignatieff: The first person to say outright when he went to America that democracy wasn’t just a system of government but a way of life was [19th-century French philosopher Alexis de] Tocqueville. And Tocqueville gets an incredibly vivid sense of that in the 1830s in the United States. But Tocqueville also sees something else, which is that American democracy has been a ferocious no-holds-barred argument about what democracy is.

I think it’s a mistake to think of democracy as an unproblematic civic creed that suddenly fell apart in the last generation. Even in 1835, Tocqueville goes to a vote in Philadelphia, a municipal vote, and notices that while in Quaker Pennsylvania, Blacks nominally have the right to vote in municipal elections, none of them show up because they’ll be beaten up if they try. And so right away he sees that democracy is a battleground about race, and soon it becomes a Civil War battle about race and about the place of states’ rights in a federal system. That’s a democratic question. It’s not just an argument about slavery. It’s an argument about democracy, about what the South should be allowed to do, how the South should be allowed to rule itself. Even until 1860, Lincoln is saying, I don’t have an objection to the idea that our federal system implies, democratically, if the South chooses slavery, a federal, democratic system can’t stop them. The only thing I feel—although I feel slavery is an abomination—the only thing I can insist upon as a federal politician is to prevent its spread to other states.

And if you then flash forward to [the rioting at the US Capitol Building on January 6,] 2021, the thing that is so important about that horrible invasion of the Capitol was the number of people who marched on the Capitol wearing American revolutionary uniforms. Not many, but enough who were saying, “Look, when the Republic is in danger, democracy requires us to rise as a people and defend institutions from corrupt capture by a criminal elite.” That’s how many of them sincerely thought on January 6, 2021—that they were defending democracy against capture by a corrupt, democratic elite. That’s not how I see it and it’s not how millions of people see it, but it is how some people, I think, sincerely saw it. That is, if you get fancy about it, any democratic system—and America is one example, but France is the other—that starts in revolution, then has an enormous difficulty keeping democratic argument peaceful because if democracy originates from revolution, then democracy can be preserved by revolution.

I’m a Canadian. Our founding was counterrevolutionary. We were created by a bunch of people who escaped the revolution in America because we didn’t want to break with Britain. We’re a counterrevolutionary society, but America is a revolutionary society. It has convulsive arguments, dangerously violent arguments, about how it should govern itself and how it should be ruled. This is a very, very bad moment of polarization, and I think it is made worse by social media, which is a whole other story. But the basic problem was seen way back in the 1830s by Tocqueville.

Coalson: I’d like to get your reaction to a quotation from an article you wrote in 2021. “We remain stubbornly and incorrigibly in a Westphalian world, in an international order of sovereign states jealous of each other's prerogatives, protective of our borders and united, to the degree that we agree on anything at all, in the defense of each of our sovereignties.” This description still seems accurate. But I wonder if you would modify it in any way now, four years later.

Ignatieff: Yes, it was an attempt to throw a certain sober, realistic, cold glass of water down the backs of those who believe there was such a thing as a rules-based international order based on human rights and global institutions and global governance and all that stuff. I think the 1945 settlement—the creation of the UN Charter and the world created by Franklin Roosevelt—was a world of sovereign states, and some states were much more powerful than others. And the United States was unusual in trying to find its role as defending a rules-based order that it had created, providing global public goods like free navigation of the seas, leading the world toward free trade. All that did encourage the creation—and the Soviets went along with it to some degree, and the Chinese were integrated into that order to some degree—but the order itself was an order of sovereign states, competitive sovereign states, each of them defending their borders, their territory, their culture, their language, their traditions, and getting whacked over the head by their electorates whenever they forgot.

What is the immigration debate in Europe about? You see this particularly in Britain. Britain signs up to the European Convention on Human Rights and that convention gives migrants rights that ordinary British people feel is privileging foreigners over native-born citizens. There’s a huge, a volcanic reaction.

Same in France, same in Germany. I’m the son and grandson of Russian refugees, so there’s nothing about refugees I don’t like, but it’s not a popular cause. And those of us who believed in a rules-based order that put some limits on state power—that is, required states to take in migrants, required states to respect the rights of non-citizens—have discovered there’s an enormous pushback from citizens whose instincts are that we need to privilege those who are like us. Some of that is racial hostility and religious hostility, but some of it is just a tension at the heart of the international order itself, which is on the one hand an order of sovereign states and, on the other, it’s an attempt to create some cosmopolitan international obligations that bind and limit the power of states.

There was a tension at the heart of that order from the get-go, and occasionally and recurrently, it explodes, and at the end of the day, the order of states wins because only states have the coercive power to make their laws stick. International tribunals, international legal systems don’t have the coercive power that states have. That’s why states in 2025 are still in place—because they have the power to punish, reward, imprison, evict, expel. And all those nasty powers are unanswerable sources of power.

So that’s the world we’re in. That’s the world that Trump likes. He likes a world in which America is unbound by international opinion, international treaty, international obligation and even alliance commitments to friends. He argues that you make America great again by striking off the chains that kept America bound, the chains of treaties, the chains of public opinion, the chains of international cooperation. In a way, he’s saying “That’s what we always were. We accepted limits on America’s power because we thought that was what it was to be a good citizen and we thought, stupidly, that it would magnify our power if we had all these nice alliances with friendly states like Canada. But, basically, when you add it up, they’re all a bunch of free-riders.”

So all of this is a wake-up call but the thing I’m arguing against is that there’s some wonderful world of liberal, transnational governance that he’s trashed. I think he’s expressing a contradiction that was at the heart of the order that was built in 1945 by FDR.

Coalson: I’d like to conclude by asking you, as a historian, how you view arguments that we are now experiencing “epochal change” comparable to the collapse of empires after World War I, or the defeat of fascism or collapse of the Soviet bloc. Do you find this kind of analysis useful or instructive? For example, some people are arguing that there’s no point in saying, Wait for the next election and we’ll go back to what was before, because now we’ve crossed some sort of epochal barrier and the old system is gone.

Ignatieff: I teach human rights, so I’ve spent 20 years of my life teaching the legal form of moral universalism—the idea that we have duties to people simply by virtue of the fact that they’re human. It’s a set of moral principles that I like because I like the idea that there’s a human being beneath all the differences of race and gender and class and religion and that there are some universal obligations that we have to all people.

I think that corresponds to a deep intuition that human beings have about their identity as creatures. That is, we are citizens of countries, and we speak certain languages and our skins have certain colors and we have certain beliefs, but beneath it, there is a human being. We then tried to put that into law after 1945 for the first time and that helped to accelerate the dismantling of empires because empires were based on, tacitly or explicitly, a sense of racial and civilizational superiority, which didn’t survive two minutes of inquiry once you adopted a universalist framework.

Universalist cosmopolitanism helped to dismantle the empires. I was born into an imperial world. If you were born in 1947 as I was, Britain had an empire, the Dutch had an empire, the French had an empire, the Portuguese had an empire. The Russians had an empire, the Americans had an informal empire. And now we’re in what I think is a genuinely post-imperial world.

But I sense there always was a conflict between moral universalism, the idea that we’re one species, one human race, and the equally compelling view that our differences define us. That is, we’re not all the same. You’re an American, I’m a Canadian; you may be Black, I may be white; you may be Christian, I may be Muslim; you may be female, I may be male. And these differences are salient, and they’re terribly important to our identities. And they are in conflict with, and in tension with, those universal ideas that sustained a lot of good things like the dismantling of empires, like the revolution of inclusion that equalized rights for gays and Black people and made things better for women. All that kind of egalitarian universalism did a lot of fantastic work in the 20th century.

I think now we’re going through a phase in which the claims of the particular, the claims of the nation, the claims of the race, the claims of the religion are now somehow much more salient to us than the universalist claims. But I see this as an oscillation between moral tensions that have been present from the beginning of my life, and I don’t think we’ve seen the end of it. I don’t see the Trump era, or the era we’re living in now, as ringing down the end of human rights, the end of moral universalism. Nothing ever ends. Ideas that have been part of European culture and Western culture and now global culture for 1,000 years—those ideas don’t die. They take a pounding. They take a back seat. They get pushed back underneath by people like Trump and Wilders and the AfD. They go underground but they don’t disappear.

And they’ll return in some form that we can’t tell. Usually, because there’ll be some outrage that makes people suddenly realize we can’t live in a world in which we regard the fate of people who have different skin or a different religion or a different gender as being a matter of indifference to us. We can’t live in a world like that. It’s dangerous to us, and it’s morally unacceptable.

I just don’t believe the pessimistic assumption that we’ve lost something morally and that explains why the world has gone to hell. What I think is happening is different. There’s an oscillation between universalist and particularist moral principles, and particularist moral principles are strongly in the ascendant at the moment.

Why? Because people are frightened, because the capitalist system is generating massive inequalities within countries and between countries. There’s a sense also that the climate is changing. We’ve unleashed technological change we don’t understand. There’s a tremendous amount of anxiety, and it produces a kind of nationalist circling of the wagons, which seems to me human, only too human, and not all that surprising. I guess I’m reacting consistently in our discussion to apocalyptic views of the future. That’s not how I see the past, and it’s not how I see the present. And it’s not how I see the future.

Michael Ignatieff led Canada’s Liberal Party in opposition from 2008 until 2011, and became president and rector of Central European University (CEU), then in Budapest and now in Vienna, in 2016, remaining in the post until 2021. The author of many books, he currently teaches history at CEU.

Wonderful discussion. Thank you for giving us a window into the "roots of our current discontent". I do found it enlightening, somewhat reassuring and disconcerting at the same time. Just to give ypically Canadian answer. The idea of the oscillations between universalism and individualism is a constant in history consistently inconsistent.

It is no great epiphany that a lot of the populism were seen today is a result, it can and has been argued, of capitalism not sharing the wealth that's generated. The gilded age on steroids. The extreme case is in the US.

History rhymes. D'torqueville was onto something in the 1830, 200 yrs later, full circle. I agree with your Articulating the argument as the partial roots of trumpism as a manifestation of the original sin of the American project, racism, (Paraphrased).

You can see why a political system rose up to block Ignatieff from power. They do not want leaders who think, have a vision, and a moral compass.